I am often asked if I eat clams. The answer is yes: while I love to observe live clams and appreciate their abilities, I will eat a good clam chowder or plate of grilled scallops if presented with the chance. While I’m generally not a fan of super fishy-tasting foods, I eat bivalves with a clear conscience because farmed mollusks represent a super sustainable way to get protein! However, as many of us have learned the hard way, shellfish can sometimes produce unwanted results later after the meal, if the animals are contaminated with food poison. Eating such “bad” clams can produce a spectrum of food poisoning symptoms ranging from vomiting and diarrhea to memory loss to even paralysis and death.

Humans have known the hazards of eating shellfish for a very long time. It has been suggested that the ban on shellfish present in kosher and halal dietary rules arose as a preventative measure to protect from food poisoning (though eating fish, land animals and even vegetables can poison people in numerous ways as well). Studies of oysters have determined that ancient peoples of modern day Georgia from 5000 years before present selected their season of harvest based partially on knowledge of the seasons when such poisoning was most prevalent in their area.

How and why does this happen, and what can we do to prevent it? It’s a billion-dollar question, because when flare-ups of shellfish food poisoning happen, they are hugely costly to fishermen and the food industry, costing millions of dollars a year in lost business when fisheries are forced to shut down and products are recalled. Such events are increasing in frequency and severity. Which makes it all the more strange that these shellfish poisoning events are not the fault of the bivalves per se, but rather what they’re eating.

Almost all bivalves are filter-feeders, using their gills to gather small passing food particles, which they then either ingest or discard based on the quality of the food item. Clams are cows crossed with Brita filters, and for many species of clams which we eat, the reason they do all this filtration is to find phytoplankton food. Phytoplankton are microscopic algae suspended by ocean currents that make their living from photosynthesis. They are a hugely plentiful and high-quality food item, making up a huge amount of the biomass available in the ocean. Like plant-life on land, phytoplankton are highly seasonal in their appearance, rising and falling in abundance in periodic “bloom” events.

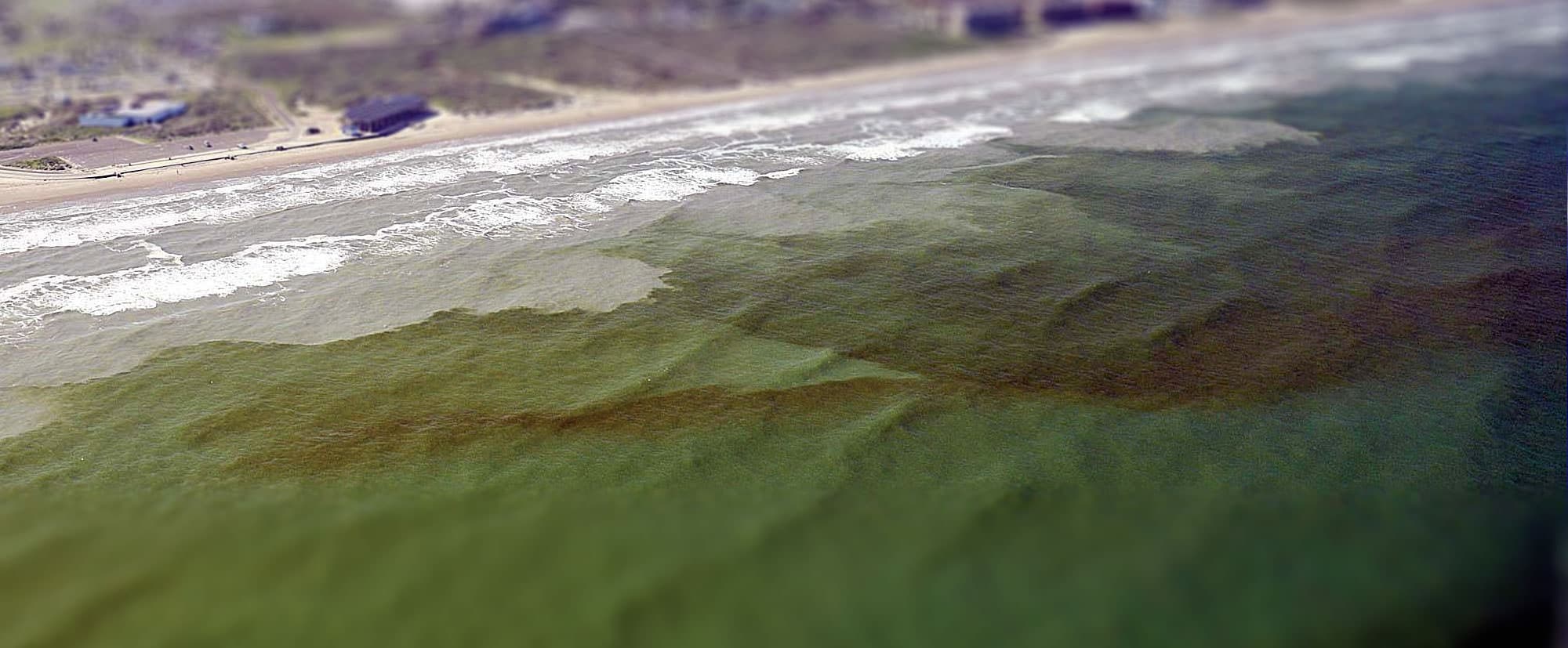

But as Spongebob Squarepants taught us, plankton are not always peaceful. Many types of algae produce toxic compounds which may be integrated into the body parts of bivalves that eat them. Scientists call the blooms of algae which produce toxins “Harmful Algal Blooms” (HABs), and such events are growing in frequency and cause huge harm to marine life and sicken thousands of people per year. There are many algae species which cause HABs all around the world, sometimes visible as “red tides,” but not always. When HABs occur, they can lead to mass deaths of higher animals in the food chain that feed on clams such as marine mammals and seabirds. In fact, HABs are at their most dangerous to humans when they catch us by surprise.

When humans eat bivalves which have been dosed with such marine toxins, many types of poisoning can occur. Brevetoxin is produced by a type of dinoflagellate phytoplankton Karenia as well as other species, and when humans are exposed, we can suffer from Neurotoxic Shellfish Poisoning, which causes vomiting, diarrhea and even neurological effects like slurred speech. Saxitoxin is produced by a variety of plankton species including dinoflagellates and freshwater cyanobacteria. When ingested in clams (such as the butter clam Saxidomus which gave it its name), fish or other animals, it can cause Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning, a sometimes fatal syndrome which shuts down nerve signaling, leading to temporary paralysis.

So we know it’s bad for humans to ingest these toxins. What is it doing to the clams? Oddly enough, some types of toxins like saxitoxin are not that harmful to the clams or other plankton eating animals, allowing them to accumulate huge amounts in their bodies with little ill effect. Its presence does not seem to influence their feeding behavior much, or their growth after exposure. Its status as a neurotoxin in mammals might be a total chemical and evolutionary coincidence, as researchers suggest that it may actually serve as a signal in some part of the algae’s mating cycle. This also may be the case for brevetoxin, which appears to be produced when Karenia is under environmental stress. But there is not much agreement in the HAB and aquaculture research fields, because there are many types of algae, which may produce their toxins for many reasons, and it is very hard for us to zoom in to the scale of the microbe and out to the scale of the ecosystem at the same time, to find any kind of universal evolutionary role of these toxins. Some researchers insist that some bivalves are influenced negatively by brevetoxin, but only at the juvenile stage during major bloom events. The effects of the toxin may only influence certain species, or only become significant if the toxin reaches the digestive tract of the bivalve. Overall, research into impact of HABs on clams is still a topic of active research, and the idea that the microbes produce these toxins to defend against bivalve predators is definitely not a slam-dunk, easily proven hypothesis. While some clams are negatively affected by the toxins, it is not consistently observed across species in a open-and-shut way, and it can be a subtle effect to observe and quantify scientifically.

The more I read about this stuff, the more shocked I am at the incredible complexity of marine algae and their toxins. I only started reading about them trying how to to understand how they influence bivalves. I was hoping to find some evidence of their effects on bivalve growth that I could apply back in time in fossil shells to understand the historical occurrence of HAB events. It’s important to understand HABs because they hurt people, cost our society a lot of money and if we understand how to avoid them, we can help minimize such impacts in the future as HABs continue to become more common.

Very interesting!

LikeLike

Why do I get a black Tongue and teeth from eating clam chowder?

LikeLike

I am sorry to say I have no idea in this situation! I recommend asking a doctor or dentist if they’re familiar with other cases of this!

LikeLike

Pingback: The Best Tasting Clams: A Comprehensive Guide | AnchorAndHopeSF