In undergrad, I felt like my school and internship were training me to be two different types of researcher. At USC, I was majoring in Environmental Studies with an emphasis in Biology. It was essentially two majors in one, with a year of biology, a year of chemistry, a year of organic chem, a year of physics, molecular biology, biochemistry, etc. On top of that, I took courses on international environmental policy and went to Belize to study Mayan environmental history. Meanwhile, I was working at Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena researching trends in historical rainfall data. I loved both sides of my studies, but felt like neither was exactly hitting the spot of what I would want to spend my career researching. I love marine biology but am not particularly interested in working constantly in the lab, looking for expression of heat shock protein related genes or pouring stuff from one tube into another. On the other hand, I was fascinated by the process of untangling the complex history of rainfall in California, but I yearned to relate this environmental history to the reaction of ecological communities, which was outside the scope of the project.

During my gap year post-USC, I thought long and hard about how I could reconcile these disparate interests. I read a lot, and researched a bunch of competing specialized sub-fields. I realized that paleobiology fit the bill for my interests extremely well. Paleobiologists are considered earth scientists because they take a macro view of the earth as a system through both time and space. They have to understand environmental history to be able to explain the occurrences of organisms over geologic time. I really liked the idea of being able to place modern-day changes in their geologic context. What changes are humans making that are truly unprecedented in the history of life on earth?

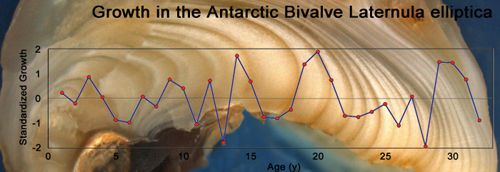

But it doesn’t have to be all zoomed out to million-year processes. A growing sub-field known as Conservation Paleobiology (CPB) is focused on quantifying and providing context of how communities operated before humans were around and before the agricultural and industrial revolutions, in order to understand the feasibility of restoration for these communities in this Anthropocene world. Sometimes, this means creating a baseline of environmental health: how did oysters grow and build their reefs before they were harvested and human pollution altered the chemistry of their habitats? I’m personally researching whether giant clams grow faster in the past , or are they reacting in unexpected ways to human pollution? It appears that at least in the Gulf of Aqaba, they may be growing faster in the present day. Such difficult and counterintuitive answers are common in this field.

Sometimes, CPB requires thinking beyond the idea of baselines entirely. We are realizing that ecosystems sometimes have no “delicate balance” as described by some in the environmental community. While ecosystems can be fragile and vulnerable to human influence, their “natural” state is one of change. The question is whether human influence paves over that prior ecological variability and leads to a state change in the normal succession of ecosystems, particularly if those natural ecosystems provide services that are important to human well-being. In a way, the application of paleobiology to conservation requires a system of values. It always sounds great to call for restoring an ecosystem to its prior state before humans. But if that restoration would require even more human intervention than the environmental harms which caused the original damage, is it worth it? These are the kinds of tricky questions I think are necessary to ask, and which conservation paleobiology is uniquely suited to answer.

At the Annual Geological Society of America meeting in Seattle this year, the Paleo Society held the first-ever Conservation Paleobiology session. The room was standing room only the whole time, investigating fossil and modern ecosystems from many possible angles. This field is brand new, and the principles behind it are still being set down, which is very exciting. It’s great to be involved with a field that is fresh, interdisciplinary, and growing rapidly. I look forward to sharing what my research and others find in the future.