Not all bivalves have a planktotrophic larval stage, though. Larvae of lecithotrophic bivalve species (“yolk-eaters”) have yolk-filled eggs which provide them with a package of nutrition to help them along to adulthood. Others are brooders, meaning that rather than releasing eggs and sperm into the water column to fertilize externally, they instead internally develop the embryos of their young to release to the local area when they are more fully developed. This strategy has some benefits. Brooders invest more energy into the success of their offspring and therefore may exhibit a higher survival rate than other bivalves that release their young as plankton to be carried by the sea-winds. This is analogous to the benefits that K-strategist vertebrate animals like elephants have compared to r-strategist mice: each baby is more work, and more risky, but is more likely to survive to carry your genes to the next generation.

Brooding is particularly useful at high latitudes, where the supply of phytoplankton that is the staple food of most planktrophic bivalve larvae is seasonal and may limit their ability to survive in large numbers. But most of these brooding bivalves stay comparatively local compared to their planktonic brethren. Their gene flow is lower on average as a result, with greater diversity in genetic makeup between populations of different regions. And generally, their species ranges are more constricted as a result of their limited ability to distribute themselves.

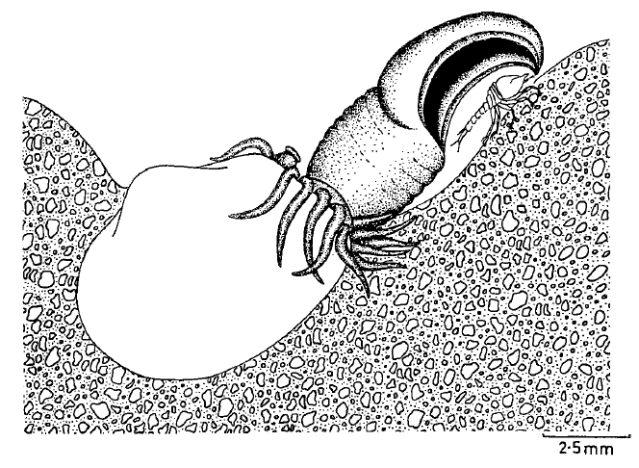

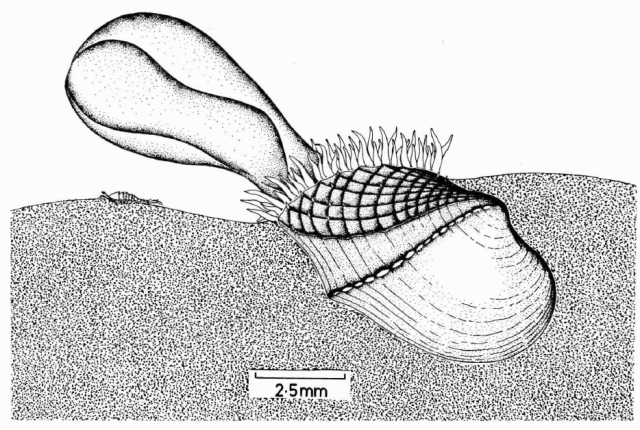

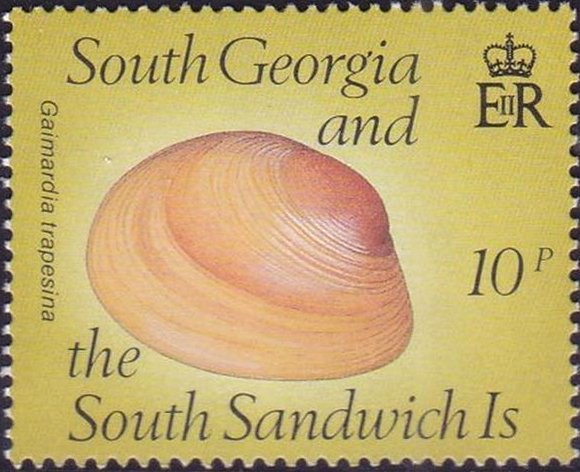

But some brooding bivalves have developed a tool to have it all: they nurture their young and colonize new territories by sailing the seas using kelp rafts. The clam Gaimardia trapesina has evolved to attach itself to giant kelp using long, stringy, elastic byssal threads and a sticky foot which helps it hold on for dear life. The kelp floats with the help of gas-filled pneumatocysts, and grows in the surge zone where it often is ripped apart or dislodged by the waves to be carried away by the tides and currents. This means that if the clam can persist through that wave-tossed interval to make it into the current, it can be carried far away. Though they are brooders, they are distributed across a broad circumpolar swathe of the Southern Ocean through the help of their their rafting ability. They nurture their embryos on specialized filaments in their bodies and release them to coat the surfaces of their small floating kelp worlds. The Southern Ocean is continuously swirling around the pole due to the dominance of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, which serves as a constant conveyor belt transporting G. trapesina across the southern seas. So while G. trapesina live packed in on small rafts, they can travel to faraway coastlines using this skill.

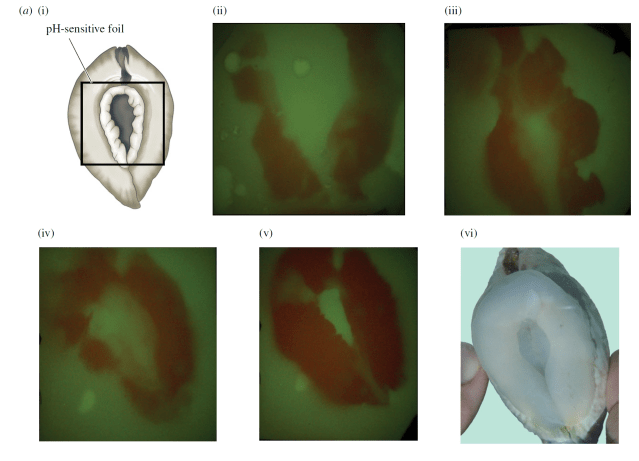

The biology of G. trapesina was described in greater detail in a recent paper from a team of South African researchers led by Dr. Eleonora Puccinelli, who found that the clams have evolved to not bite the hands (kelp blades?) that feed them. Tests of the isotopic composition of the clams’ tissue shows that most of their diet is made up of detritus (loose suspended particles of organic matter) rather than kelp. If the clams ate the kelp, they would be destroying their rafts, but they are gifted with a continuous supply of new food floating by as they sail from coast to coast across the Antarctic and South American shores. But they can’t be picky when they’re floating in the open sea, and instead eat whatever decaying matter they encounter.

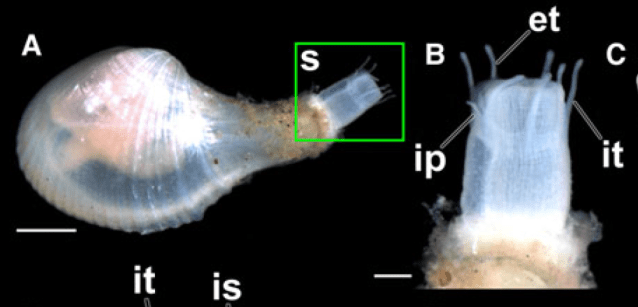

The clams are small, around 1 cm in size, to reduce drag and allow for greater populations to share the same limited space of kelp. Their long, thin byssal threads regrow quickly if they are torn, which is a useful skill when their home is constantly being torn by waves and scavengers. Unlike other bivalves, their shells are thin and fragile and they do not really “clam up” their shells when handled. They prioritize most of their energy into reproduction and staying stuck to their rafts, and surrender to the predators that may eat them. There are many species that rely on G. trapesina as a food source at sea, particularly traveling seabirds, which descend to pick them off of kelp floating far from land. In that way, these sailing clams serve as an important piece of the food chain in the southernmost seas of our planet, providing an energy source for birds during their migrations to and from the shores of the Southern continents.