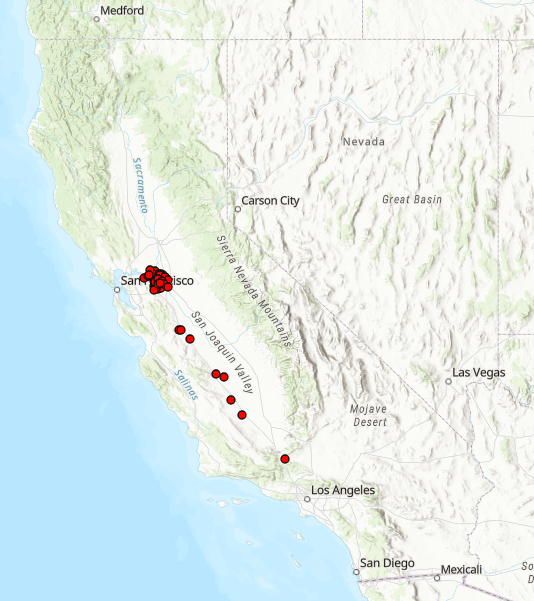

I legitimately admire clams. I whole-gilledly believe that they do a lot of good for the world; way more than we do! But there’s no doubt that some types of clams are up to no good, thanks to our help. One of those species is Limnoperna fortunei, the golden mussel. In late 2024, this species was observed for the first time on the North American continent, found attached to various human infrastructure in the Sacramento Delta of California. Since then, it has made its way down the California aqueduct all the way to the Southern tip of the Central Valley. Golden mussels are a notorious invasive species, and California officials immediately recognized the potential for disaster here, leading to dramatic policies of containment throughout the state that have tremendously impacted the lives of people trying to enjoy life on the water.

Since we are in uncharted waters with these mussels, there are a lot of questions about these innocuous-looking but trouble-making clams. In this blog, I will try to answer some of the most frequent questions I’ve seen over the last few weeks. I will caveat this by saying that I currently have no active research on this species, but I am a card-carrying clam scientist, and have a lot of interest in its biology and the significance its presence it will have for our state. So let’s get into it!

What are golden mussels? Where are they originally from? How did they get here?

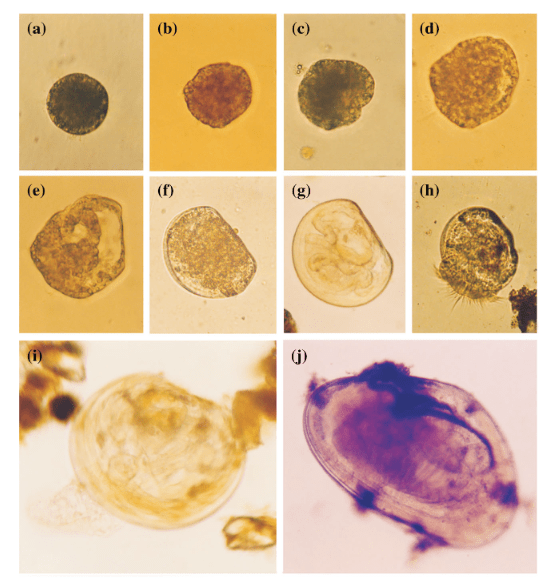

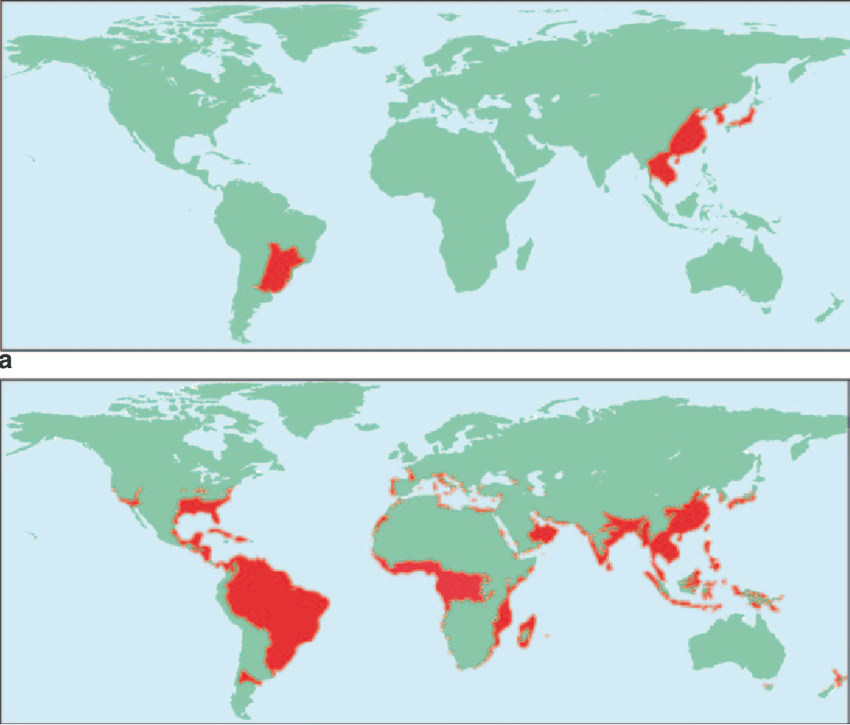

Golden mussels are small mussels, only reaching a bit over an inch in length, native to the Pearl River basin in China (the area around Hong Kong and Macau), but have been spread around the world over recent decades with the help of humans, hitching a ride between continents in the ballast water of our ships. Once settled in a new place, they easily move between lakes attached to boats being driven around, since they can live up to ten days out of water (talk about holding their breath!). The mussels first spread throughout Southeast Asia, then to Japan, then South America, and now for the first time, to the North American continent. While they are true mussels, in the same family (Mytilidae) as the more famous saltwater mussels you might have seen in tide pools, they can’t tolerate fully marine conditions.

Why are they a problem?

Golden mussels are prolific breeders and make a living by anchoring themselves to any available hard surface using byssal threads. This is relatively uncommon among freshwater bivalves, most of which live on the bottom and don’t attach to surfaces. Golden mussels reproduce by releasing thousands of tiny larvae which spread through the area on river currents. In areas where they attach (such as dams, aqueducts, boats and other infrastructure), they form dense colonies that gum up the works, clogging pipes and and coating surfaces with thousands of their sharp little shells. They can even attach to the roots of native plants and shells of other molluscs and smother them! This causes hundreds of millions of dollars in damages and continuing expense in reservoirs and irrigation systems where they’ve taken hold, like in Japan and South America. If the mussels were to unexpectedly clog the outlet of a Californian reservoir like Lake Berryessa or Folsom Lake, it could be disastrous for people who depend on that water.

Quagga and zebra mussels, originally from Central Asia, are invaders in the Colorado River, the Great Lakes, and reservoirs in Southern California. They have been limited from spreading into most reservoirs in Northern California by the low calcium content of lakes here (a function of our local rocks and geology). But golden mussels have lower calcium requirements than zebras/quaggas, so it is likely that they can reproduce in reservoirs up here. They are also surprisingly resistant to low temperatures, meaning that they could potentially take hold in high-altitude lakes like Lake Tahoe, which could be a disaster for efforts to keep Tahoe blue.

Why are they so successful?

Being so prolific in their numbers allows the mussels to transform the chemistry and biology of the waters where they live. Like most bivalves, golden mussels make their living by using their gills to filter particles out of the water column, drawing them down to their mouth to eat. While individual golden mussels are pretty average in their filtering ability, together they work to much more effectively clear the water than other species, thereby depriving those native species of the plankton food they need, and potentially even directly eating the plankton larvae of other animals around them!

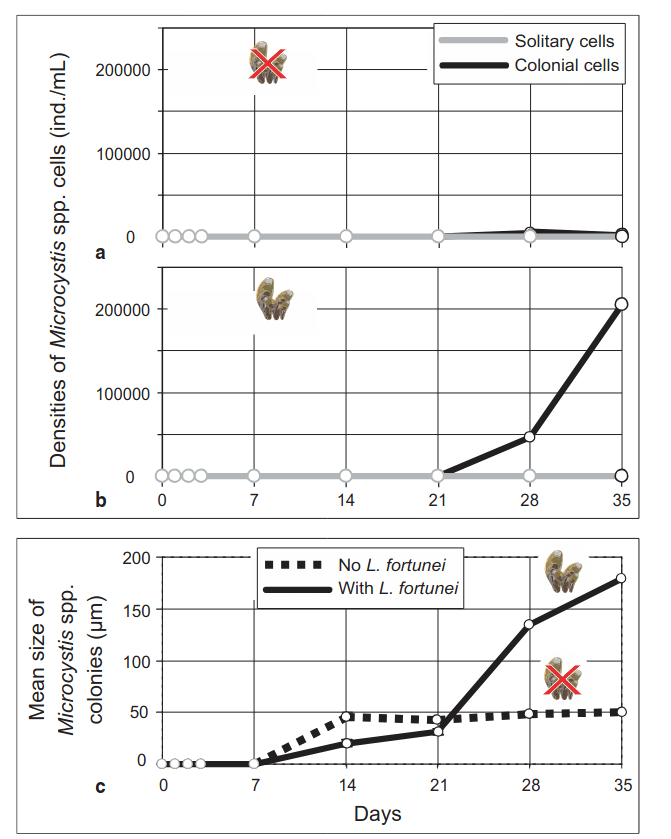

The Sacramento Delta has plenty of plankton floating around, so it’s not surprising they’ve decided this is a nice place to live. But while the water-cleaning ability of clams is a useful service they provide, there can definitely be too much of a good thing. The mussels are “ecosystem engineers”, meaning that they make the environment they want to live in. The problem is that what is good living for the mussels is not necessarily the habitat of a thriving Delta. Where they take hold, they exclude native species and generally decrease water quality by trapping dirt and boosting the populations of cyanobacteria. The Sacramento Delta already struggles with toxic cyanobacteria, and don’t need to have the problem be worse! Lower water quality means fewer fish, which is bad for people and the ecosystem.

Why have they shown up now?

This is actually not the CA Bay/Delta’s first rodeo with foreign clams. Invasions of Asian clams (Corbicula fluminea) and overbite clams (Potamocorbula amurensis) in the 1980s transformed the Bay, with trillions of clams spreading out all the way south towards San Jose and eastward into the Delta after being introduced in Grizzly Bay in the mid-1980s. These clams had enormous impacts on the ecosystem, excluding other bottom-dwelling animals and eating most of the plankton food that other animals rely on. They are thought to have played a major role in the decline of some native fishes like Delta and longfin smelt.

Golden mussels have been making their way around the world over the decades. It is hard for their larvae to survive a couple weeks in the belly of a ship, be released, and successfully take hold, but with enough ships coming to California, it was only a matter of time before all of the stars aligned and a population took hold. We don’t know if the appearance of golden mussels will push out Asian clams, or if they’ll coexist. Asian clams live on the bottom rather than attaching to stuff, but golden mussels may still compete with them for food.

Are there other ways they spread?

Previous studies investigating their spread in South America and Japan determined that virtually all of their spread happens attached to the hulls of ships, in ballast water, or anywhere their larvae can travel downstream. There are rare cases where they are believed to travel upstream in the guts of fish that eat them, being pooped out alive. But those are unusual cases. That also won’t help them spread past dams without a fish ladder. The planktonic larvae have very little ability to swim against the current, so they won’t be able to swim upstream through dam turbines.

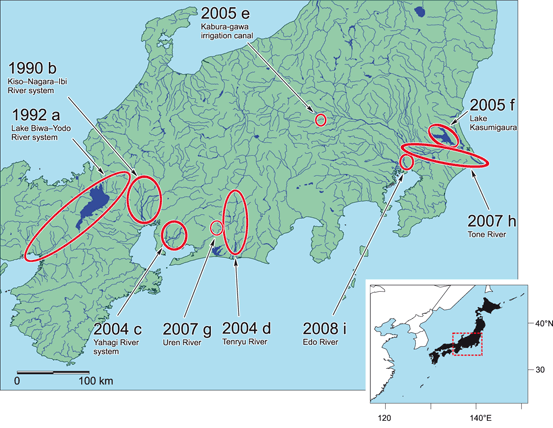

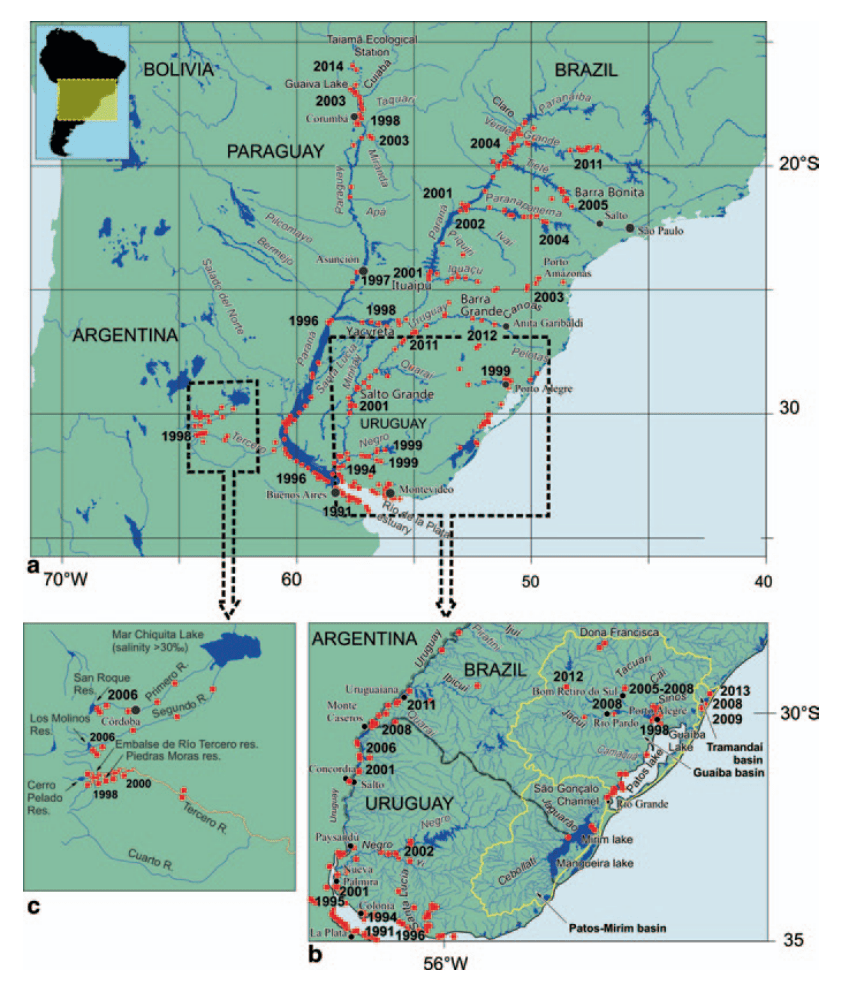

Unlike pea clams, which are famous for attaching to birds by clamping their shells on their feet or feathers and traveling long distances to reach new places, it is not believed that golden mussels can create their thread attachment fast enough to hitch a ride on birds (which is a process that takes hours). So fortunately, I can assure our avian friends that we won’t need to inspect them before they use our reservoirs. At the end of the day, human vessels are the main way these mussels are getting around to far-flung places. In Japan, it took around 15 years to spread river to river through the country, while in South America, it covered most of a large area from Buenos Aires to Southern Brazil in that same period of time, which was proposed to be largely due to greater boat traffic in South American rivers.

Are they good eatin’?

These mussels weigh only a little over an inch at best, with not much meat on them. Unlike Asian clams (Corbicula), which are eaten in some Asian cultures, I can’t find mention of anyone eating golden mussels. There have been attempts using them as a fertilizer calcium supplement, but that needs more research. Additionally, it’s known that the other invasive clams of the Bay/Delta are concentrators of toxins, including selenium from farm runoff, heavy metals, and also toxins from harmful algae. In places where golden mussels colonize, toxic cyanobacteria can proliferate, so they actually make themselves a bit more toxic than other clams in the same place would be!

What can we do about them?

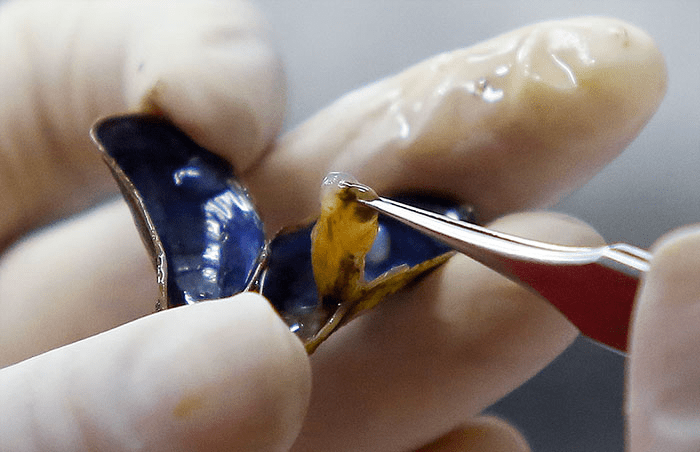

We just don’t know how L. fortunei will fare long term in the California Delta and lakes. The previous clam invasions have waxed and waned through time. It’s uncertain whether these mussels will fizzle out, as sometimes happens for invasive species, or if they’re here for the long haul. The speed of their spread throughout the state personally leads me to suspect they’re here for good. And in the meantime, the invasion has caused huge issues for anglers, boaters and dam operators throughout California this summer, who have had to institute boat inspections at every reservoir in the state. Boats have to be painstakingly checked for mussels stuck to surfaces on the hulls.

Eventually, it is possible that mussels will find their way through, despite these precautions. Some could be missed in the crevices of boats entering various reservoirs. But hopefully that will buy time for dam operators to put forth the needed upgrades and develop procedures to keep them from fouling dams and aqueducts. At that point, the objective becomes mitigation rather than prevention. It won’t be cheap, usually involving manual scraping of mussels off of surfaces, application of hot water, pesticides, and use of surfaces that discourage mussel growth.

Long-term, our invasive species management needs to be more proactive rather than reactive. California was previously recognized to be in the range of territory where golden mussels could appear (see figure above). We can’t allow future invasions to catch us by surprise. To that end, there are laws on the books in California requiring inspection of 25% of incoming ships. So far, we are only inspecting a small fraction of that number. Additionally, ships were previously required to release ballast water far offshore in the ocean, where freshwater species wouldn’t be able to get a foothold. That policy was also not adequately enforced, and requirements to sterilize ballast water with chemical treatments were ruled too expensive. The state government very recently strengthened the standards, but gave ships until 2030 to comply with a weakened version of the rules, and pushed off compliance with the final strongest version until 2040!

People frustrated about such invasive species in California should insist to their policymakers that we can and must do better. There are many more invasive clam species waiting for their chance at a ride over here to make a living in our waters. It’s not too late to stop the assembly line of species coming to displace the native creatures we all love and value!