You might be familiar with the concept of the present “biodiversity crisis“. There is an increasing consensus in the ecological research community that the current loss of species this planet is experiencing is not sustainable, in the sense that the loss of some species may precipitate the loss of more, in an accelerating spiral. The paleontological community has found that the pattern of species loss is unusual even at the scale of geological time, potentially placing us among the great extinctions in geologic history, or at least a notably bad extinction event. A less diverse biosphere means the loss of ecosystem services associated with all of the species we lose, and potentially a less resilient biosphere, stacking the deck against us as the climate continues to change and life is forced to adapt. Because our global civilization depends on the wealth of the biosphere for our own well-being, this is definitely very bad news for humanity (I usually tend to avoid rationalizing conservation based on ecosystems’ value to us, believing that we have a moral imperative to preserve the biosphere, and organisms have an inherent right to exist outside of their economic value, but that’s a topic for another blog).

We are only aware of the loss of species due to centuries of careful collecting, cataloging, categorization and curation undertaken by conservationists around the world, including indigenous communities, museum professionals, taxonomists, seed banks, herbaria, and other very highly specialized and educated people. I won’t refer to these biodiversity experts as “countless”, because they’re actually a pretty small group of folks entrusted with an almost incomprehensible responsibility: to quantify the biological wealth of our world. They figure out when baselines are shifting, and their work keeps us accountable as we seek to stop the current bleeding of biodiversity.

I am writing this post because biological collections are having a moment of attention, and it’s been a topic I have been thinking of for some time as an outsider. Duke University recently announced that they will be throwing out their herbarium, an archive of plant samples which is one of the leading such collections in the US. The herbarium supports a vibrant ecosystem of research on the classification of plants, and is an important archive of plant diversity. Duke University, which has an endowment of $11 billion, claiming to not have the resources to support this archive is an unacceptable dereliction of their duty to preserve and nurture knowledge. And sadly, this closure of such an important collection is not a one-off event. Worldwide, taxonomist and curator jobs are declining. These are the people who spend decades learning how to tell one species of snail from another based on their genitalia. They discover cryptic species in collections. They prevent collections from degrading due to improper preservation, and charge in to save samples from fires. They process loans and when someone like me is belated in returning samples, they write a polite email reminding me to send samples back. When these people leave science, their skills can’t be easily replaced. If collections are lost, they literally can’t be replaced.

I am a biogeochemist, and not a museum worker by any means, but so much of my work has relied on biological archives. But by my count, 3/4 of my ongoing projects have used biological collections in some way. I wanted to list out some of the ways that biological collections have enabled my research, because I don’t think I’m unusual. Biodiversity curators are the keystone species in a vast ecosystem of interconnected research that wouldn’t happen without the hard work of maintaining collections. Please do what you can to protect biodiversity collections, whether by pressuring your representatives, your alma maters, and through donations.

Projects that relied on curators:

- Some of my most influential educational experiences relied on teaching collections, including at Cabrillo Marine Aquarium, USC, LA Museum of Natural History, UC Santa Cruz and elsewhere. Without collections to get my hands on in lab exercises and other educational opportunities, my skills in ecology, organism ID and more would be greatly diminished.

- My second PhD chapter relied on samples of well-preserved Jurassic lithiotid bivalves which came from outcrops which mostly no longer exist, having been quarried out or already sampled. These were loaned by curators at the University of Padova and University of Verona Natural History Museums

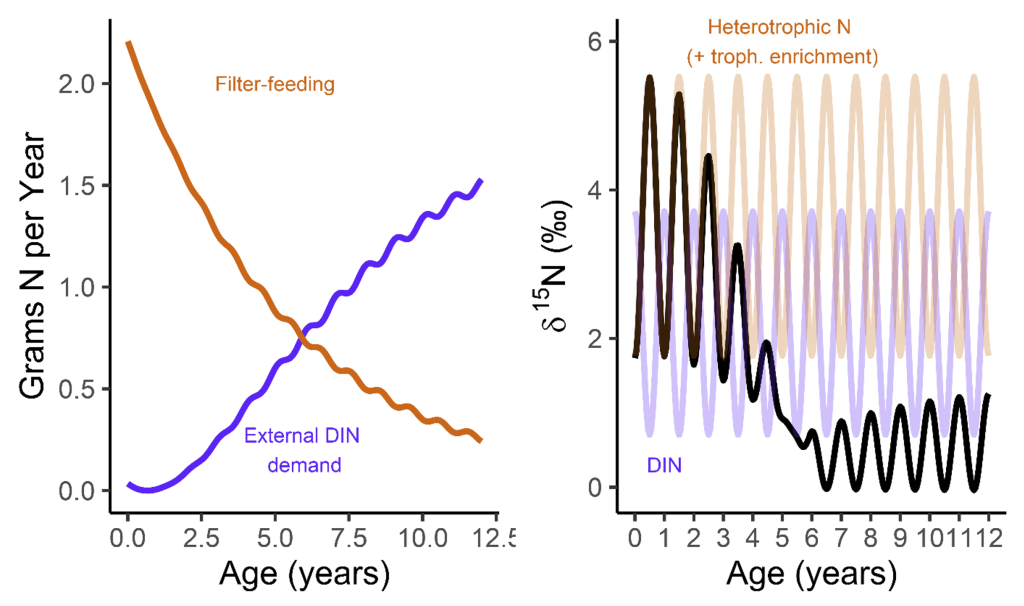

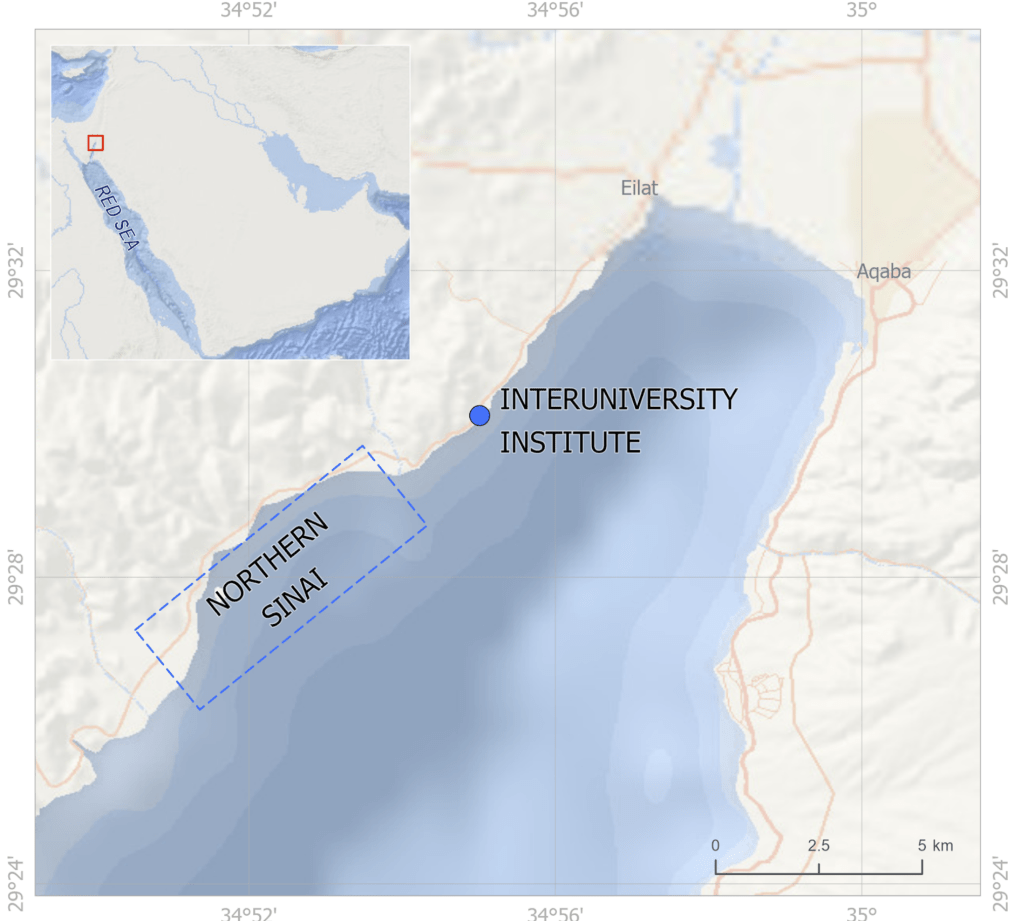

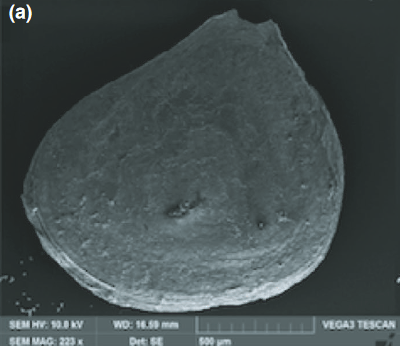

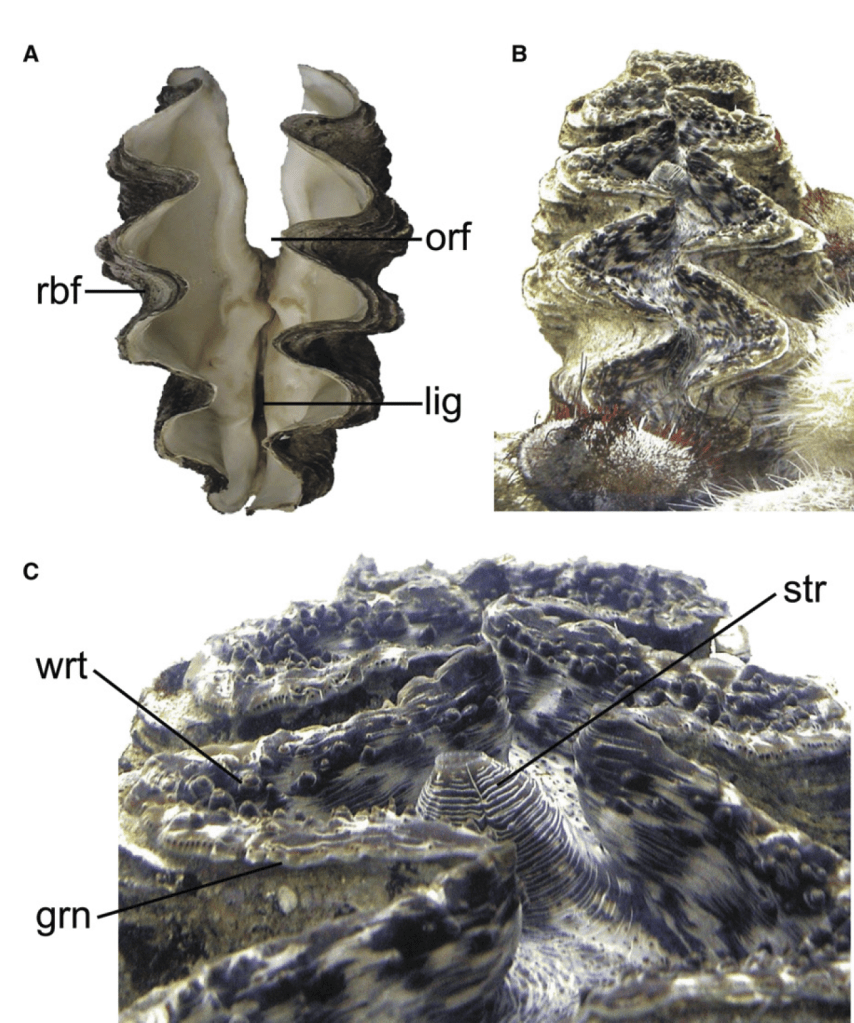

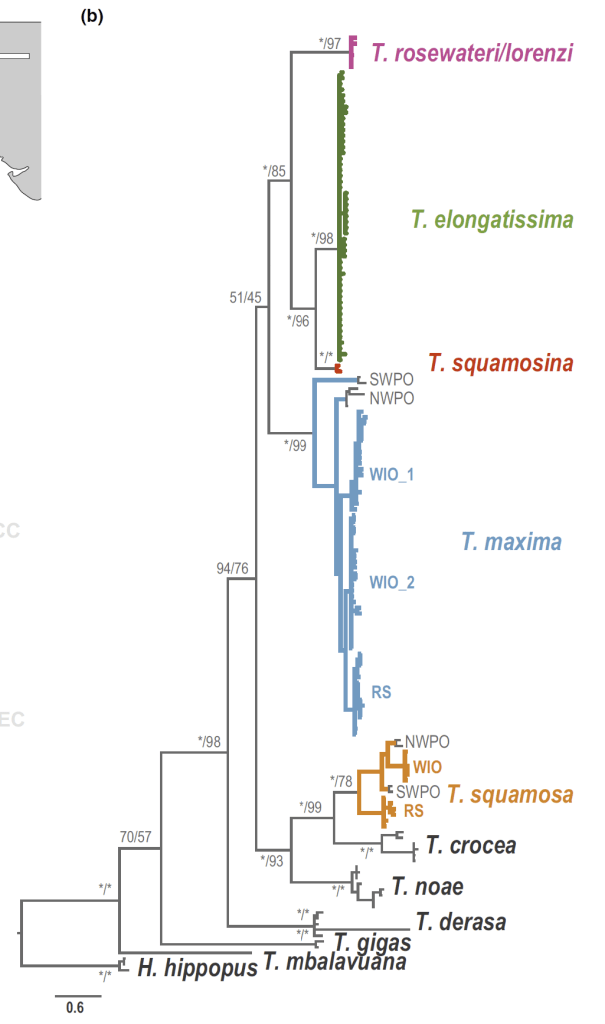

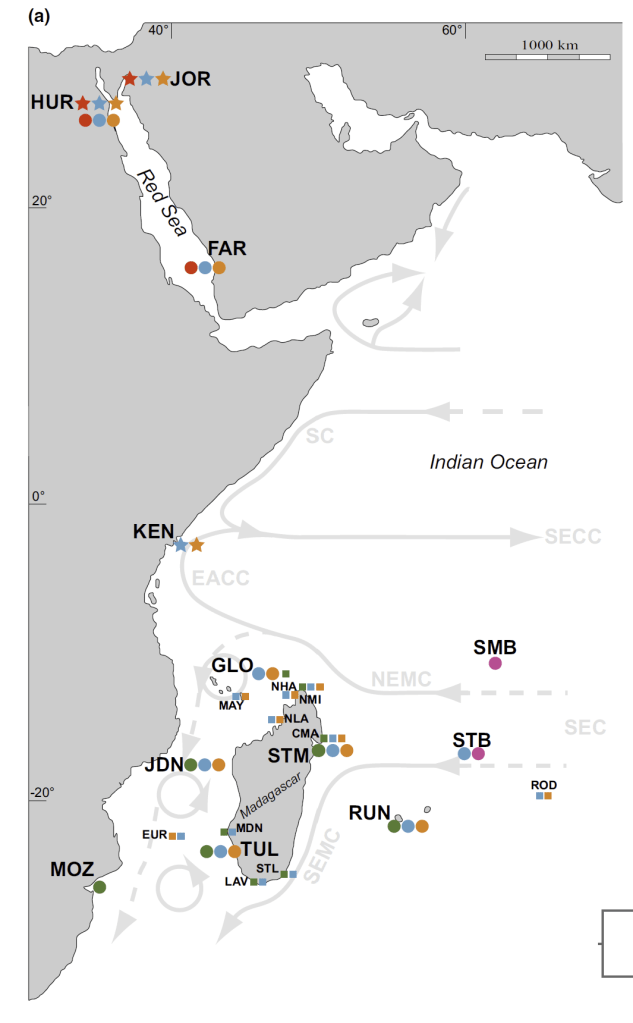

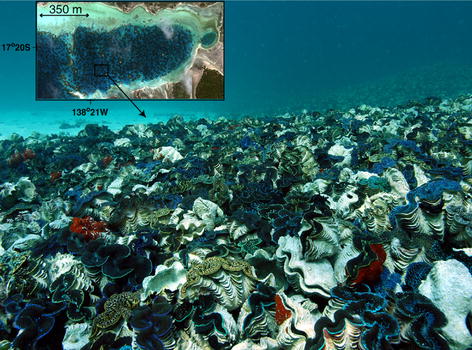

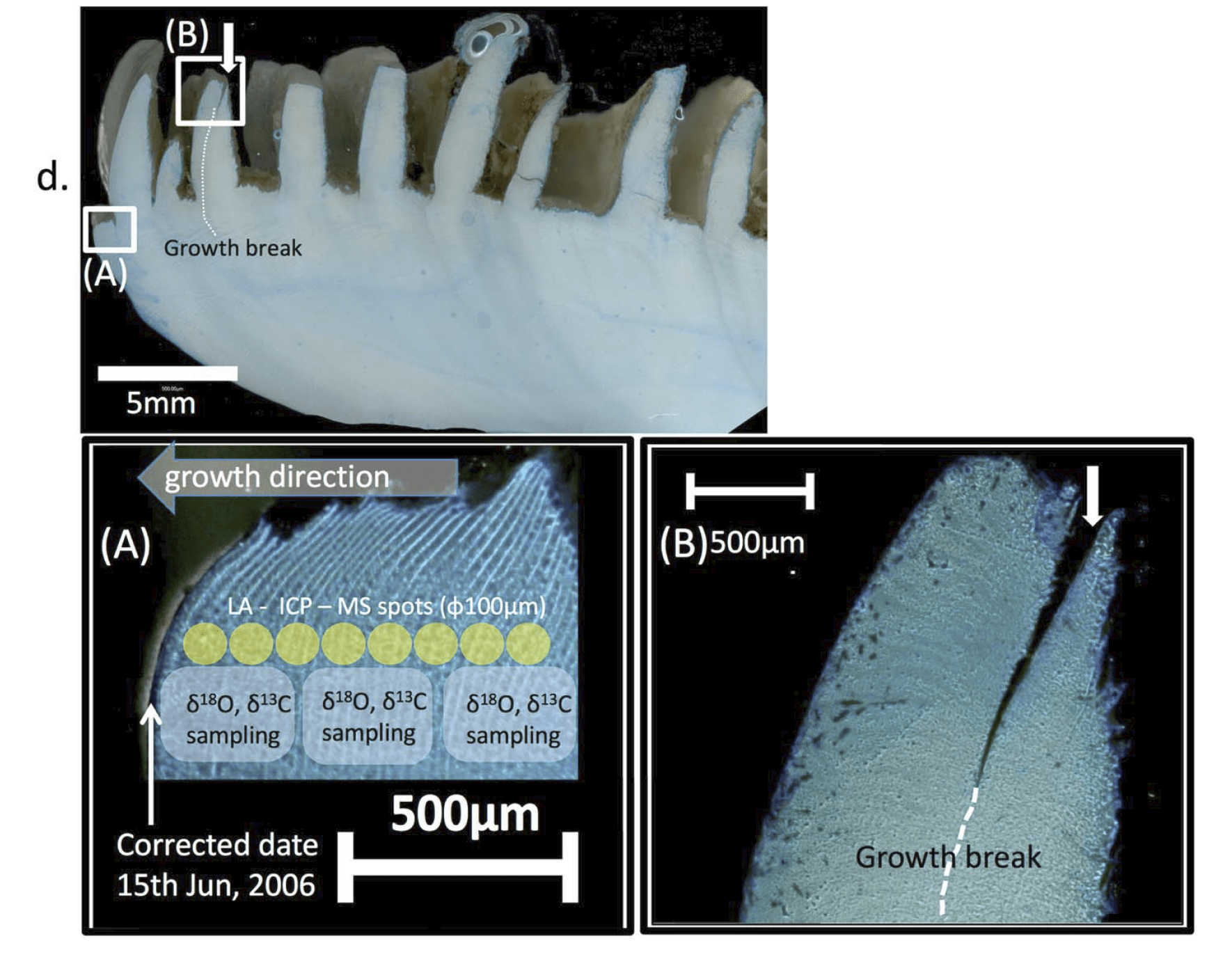

- My third and fourth PhD chapters, and one of my postdoctoral papers used shells of giant clams that were stored at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem Natural History Museum. These shells had been confiscated from poachers at the Egypt-Israel border and were loaned to me by curator Henk Mienis. I would rather these clams be still alive in the Red Sea, but at least we were able to use these for a series of papers about their ecology and physiology.

- Before my PhD fieldwork in Israel, I visited the California Academy of Science collection to view shells of Red Sea giant clams and practice species ID using a taxonomic key. I would also note that one of the species I have studied, Tridacna squamosina, is named because of the work of museum curators at University of Vienna.

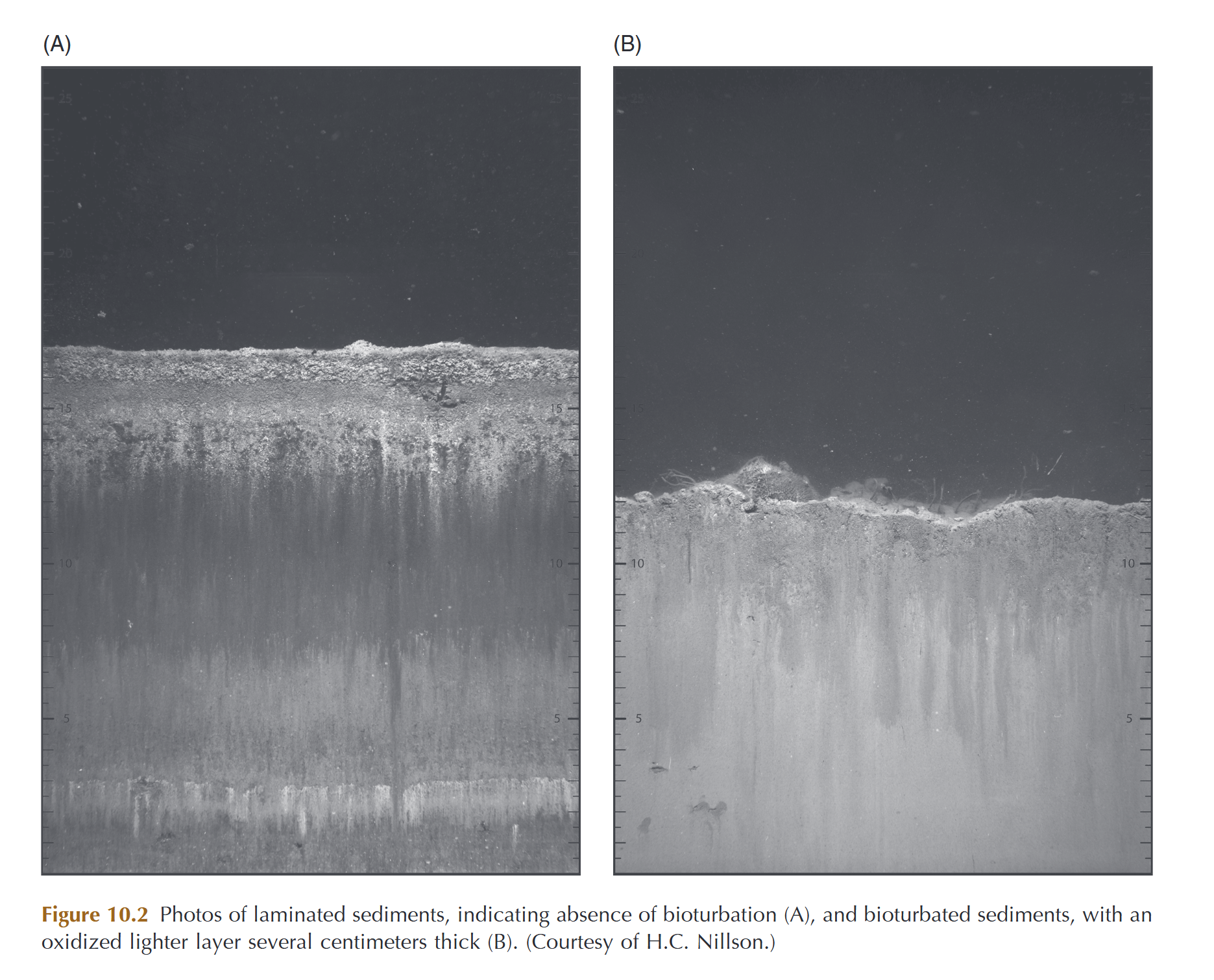

- Another postdoctoral paper (in progress) on violet bittersweet clams from the Eastern Mediterranean made use of preserved samples collected during research cruises off the coast of Israel in the 1960s-1980s. These specimens, loaned by the Steinhardt Museum in Tel Aviv, represent some of the last observed live violet bittersweets seen off of Israel. They since have (likely) gone extinct in the region, probably due to sediment changes in the late 1980s following the construction of the Aswan Dam.

- Yet another postdoctoral paper in progress resulted from study of the growth and chemistry of shells of wavy turban shells loaned from the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, which we were comparing to individuals that grew in the hot waters of the Biosphere 2 tropical reef ocean tank. I met the curator Vanessa Delnavaz at the Southern California Union of Malacologists 2021 meeting, which was hosted by the museum. Museums are important centers of scientific organization and networking in addition to the value of their collections!

So I hope all of these anecdotes help make clear that biological collections are absolutely vital to enable an entire universe of research, and that we often can’t possibly predict what collections are going to be useful for which scientific purposes until long after the samples were preserved. So any budgetary bean-counters (not talking about bean taxonomists) should think twice before closing any collections! This is a core responsibility of academic institutions and we cannot allow any of these collections to be lost. Fund your local biological curators! Without their hard work, we’d be flying blind in the current biodiversity crisis. They’re the heroes we need, and that our earth deserves.