Clams are traditionally the victims of the aquatic realm. With some exceptions, clams are generally not predatory in nature, preferring to passively filter feed. When they are attacked, their defenses center around their protective shell, or swimming away, or just living in a place that is difficult for predators to reach. They are picked at by crabs, crushed in the jaws of fish, and pried apart by sea stars. But some clams are sick of being the victims. They have big dreams and places to be. For these clams, the rest of the tree of life is a ticket to bigger and better things. These clams have evolved to live inside of other living things.

Pocketbook mussels, for example, have a unique problem. They like to live inland along streams but their microscopic larvae would not be able to swim against the current to get upstream. The mussels have adapted a clever and evil strategy to solve this problem: they hitch a ride in the gills of fish. The mother mussel develops a lure that resembles a small fish, complete with a little fake eyespot, and invitingly wiggles it to attract the attention of a passing fish. When the foolish fish falls for the trick and bites the mussel’s lure, it explodes into a cloud of larvae which then flap up to attach to the gill tissue of the fish like little binder clips. They then encyst themselves in that tissue and feed on the fish’s blood, all the while hopefully hitching a ride further upstream, where they release and settle down to a more traditional clammy life of filter-feeding stuck in the sediment.

Clams live in the gills of all sorts of organisms. Because they broadcast spawn, any passing animal may breathe in clam larvae which find the gills a perfectly hospitable place to settle. Sure, it’s a bit cramped, but it’s safe, well oxygenated by definition and there is plenty of food available. They also may just settle on the bodies of other organisms. Most of these gill-dwelling clams are commensal: that means that their impact on the host organism is fairly neutral. They may cause some localized necrosis in the spot they’re living, but they’re mostly sucking up food particles which the host doesn’t really care about. In addition, in crabs and other arthropods, these clams will get shed off periodically when the crab molts away its exoskeleton, so they don’t build up too heavily.

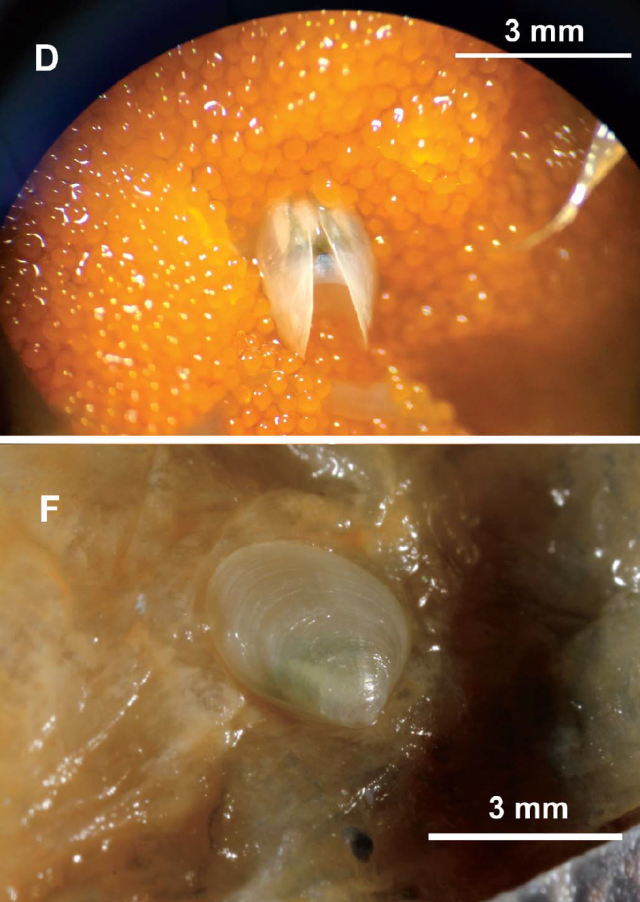

While being a parasite is often denigrated as taking the easy way out, it is actually quite challenging to pursue this unusual lifestyle. Parasitism has evolved a couple hundred times in 15 different phyla, but it is rare to find some organism midway in the process of becoming a true parasite. One team of researchers just published their observations of a commensal clam, Kurtiella pedroana, which may be flirting with true parasitism. These tiny clams normally live in the gill chambers of sand crabs on the Pacific coasts of the Americas. They attach their anchoring byssal threads to the insides of the chambers and live a comfortable life until the crabs molt, when they are shed away. The crabs mostly are unaffected by their presence, but the researchers noticed that some of the clams had actually burrowed into the gill tissue itself. This is an interesting development, because the clams would not be able to filter feed in such a location, so they must have been feeding on the crab’s hemocoel (internal blood). These unusual parasitic individuals are currently a “dead end” as they haven’t figured out how to get back out to reproduce, but if they ever do, they could potentially pass on this trait and become a new type of parasitic clam species. The researchers have potentially observed a rare example of an animal turning to the dark parasitic side of life, with some living in a neutral commensal way and other innovative individuals seeking a bit more out of their non-consensual relationship with their host crabs. Considering the irritation that other bivalves suffer at the claws of pesky parasitic crabs, this seems a particularly sweet revenge.

Pingback: Killer Clams – Clamsplaining

Pingback: A coral, a worm and some clams walk into a bar… – Clamsplaining