Recently, a bit of an amusing clamfuffel arose when the Gulf Specimen Marine Lab, a research institute in Florida, began posting about a supposedly 214-year-old clam they named “Abraclam Lincoln”, in honor of potentially sharing a birth year with Honest Abe. The story went viral, and while some of their clammy claims turned out to hinge on flawed assumptions about how clams can be aged, it was still a worthwhile opportunity to communicate about the wonderful world of bivalves with people.

I was particularly impressed with how GSML went out of their way to correct the record as more info came in. Long story short, Abraclam is not the long-lived ocean quahog Arctica islandica (more on them below), but in fact a specimen of the southern quahog Mercenaria campechiensis, which lives along the Gulf coast and grows much more quickly than A. islandica. So the large clam they found was likely more like 40 years old, which is not too unusual for this species, rather than two centuries old. It also makes much more sense to find Mercenaria in Florida than Arctica. Additionally, external shell growth lines in Mercenaria are known to not be reliable for aging the species. The shell would have to be cut open to view internal lines to figure out how old Abraclam really is, which would require killing them. Fortunately, they released the clam rather than cut them in half for science.

For what it’s worth, I still think Abraclam is an interesting specimen of M. campechiensis– they have a huge scar in their shell that would be interesting to learn more about (maybe they were hit by a dredge in their youth, healed the break and recovered to reach a ripe old age), and an unusual undulating margin at the edge of the shell that could be a deformity reported in the past literature for this species. Sometimes, scientists are wrong the first time, but we’re open about how we’re wrong, and everyone ends up learning more than we would have known otherwise.

So far so good. Then a bull had to wander into this delicate china shell with the entry of Stephen Colbert into the debate. I’ll let Stephen speak for himself, but needless to say, after his rant I feel a need to respond:

Before I dig into this clambake, Stephen, kudos to you for covering the whole story and not just the initial incorrect information. You addressed all the big inaccuracies, from the size not being tremendously out of the ordinary, to the incorrect species ID, to the incorrect age. Maybe it’s not so bad that people are getting their news from comedians rather than the news media these days! But while there were definitely some pearls of wisdom within your monologue, I have to point out some misconceptions here.

“The only thing more heartbreaking than the lies we were fed in this story…is growing up to be a clam expert!”

– Stephen Colbert

This is just plain false, since I’m not heartbroken, because clams are frickin’ awesome. Clams are way cooler than you or me, and that means by extension that the people who study them are pretty cool and interesting too (not really referring to myself. I’m just an eclamgelist along for the ride). So here are three facts about big old clams, and information about the clam experts who discovered these facts!

The ocean quahog lives to >500 years old!

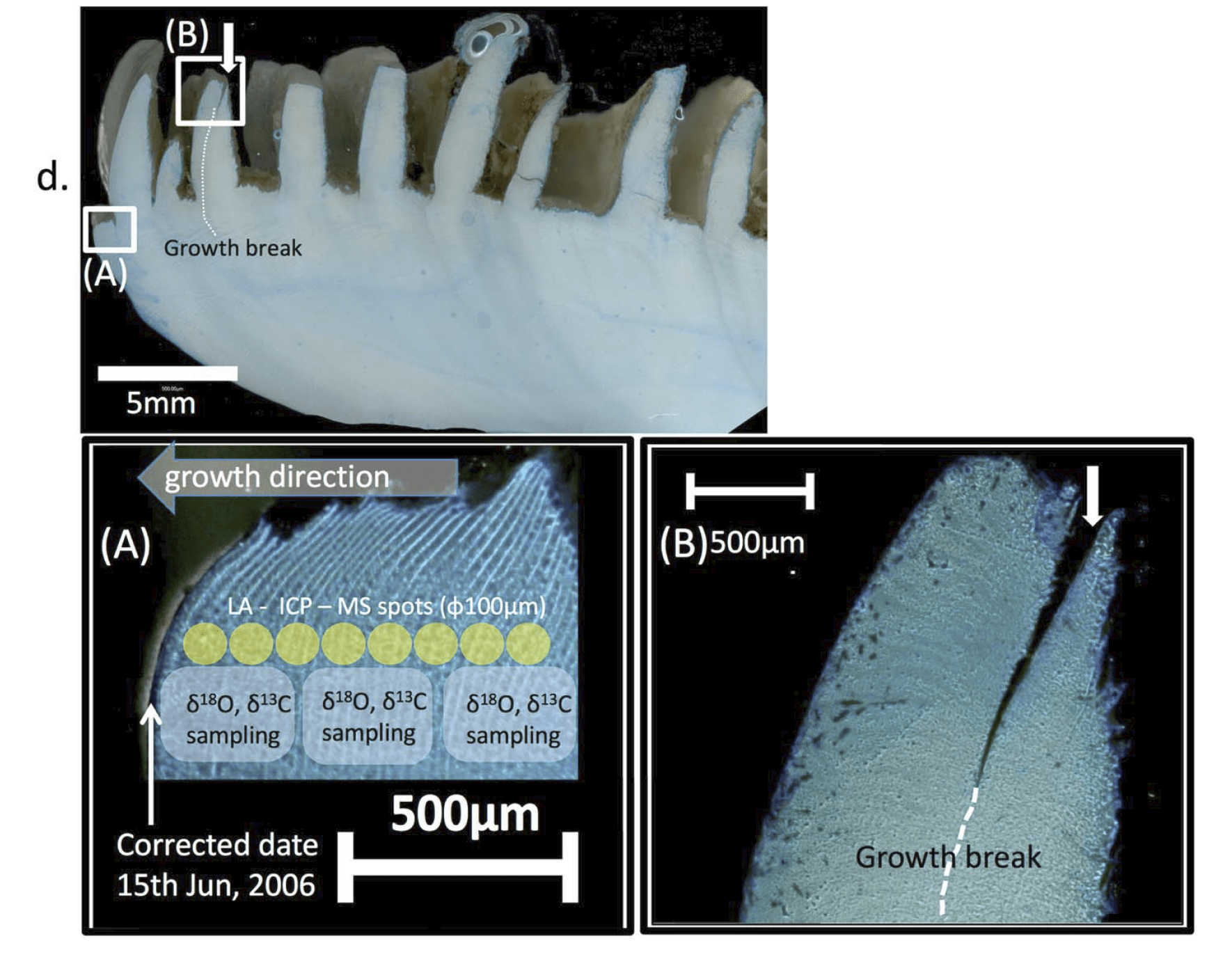

The ocean quahog Arctica islandica (which Abraclam was initially misidentified as) is tremendously long-lived, one of the longest-lived animals on earth! It has been confirmed to live to at least half a millenium! One individual caught off the coast of Iceland was aged to ~507 years by counting tiny growth lines in its shell via microscope, combined with radiocarbon dating. This clam was named Hafrún (meaning “ocean mystery” in Icelandic), but is sometimes called Ming due to it being born in the Ming dynasty of China. So put that in your Ming vase and smoke it Colbert!

Several scientists worked on aging Ming, but Alan Wanamaker at Iowa State was a lead author on the original work. He uses growth lines in the shells of many clam species as records of climate change and is generally one of the nicest people you could have the opportunity to meet.

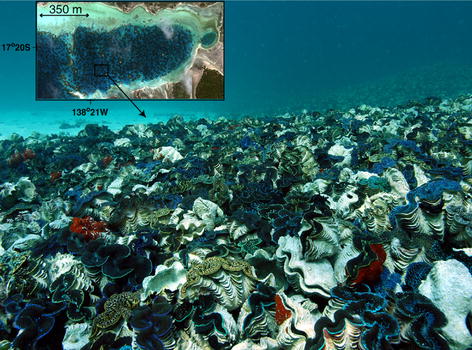

Tridacna gigas grows to over 4 feet long and hundreds of pounds!

Abraclam might be only 6 inches long (which is respectable as he/she is quite girthy; length isn’t everything, Stephen!), but there are other types of clams that are bigger than one Colbert in mass. The giant clam Tridacna gigas grows to over 4 feet long and weighs hundreds of pounds. They live on tropical coral reefs and use the power of the photosynthetic algae in their flesh to speed up their growth. So basically these clams are bigger and way more interesting than you, Stephen, since they get to go out and tan in the sun for lunch while you have to gobble down a slice of pizza.

Mei-Lin Neo at University of Singapore is considered the world’s leading expert on Tridacna, and has done more than almost anyone I know to describe all twelve currently known species of giant clams found around the world. She’s a tremendous advocate for giant clam conservation and gave an outstanding TED talk about them to boot. You should have her on your show to be honest.

Geoducks: they looked like that first!

Speaking of girthy, long clams, I’d be remiss not to mention the geoduck, Panopea generosa. Pronounced “gooey-duck,” these clams looked like this long before any part of human anatomy existed, having been around in various forms since at least the Jurassic. They have a long siphon that they use like a snorkel when they dig deep in the mud, and they can live for almost 200 years.

Brian Black at the University of Arizona is an expert in using their shells as a record of climate change. He was part of a group that was able to stitch together the growth line records from multiple geoduck shells to make a continuous record of climate change going back to 1725. Seems appropriate to note that 1725 was the year that Casanova was born…a man who may have channeled some qualities of geoducks.

Local experts on Abraclam

I’d like to mention two of the experts who corrected the record about Abraclam Lincoln and provoked Stephen’s attack in the first place. Dr. Dan Marelli wrote an op-ed correcting the record on how Mercenaria clams are aged for the Tallahassee Democrat. He’s an expert scientific diver and has published papers on clams ranging from endangered scallops to invasive mussels. Scientific diving is crucial to understand clams in their native environment, and to assist in their conservation. If I had to choose who had more interesting stories at the bar, it’d be an easy decision to listen to the swashbuckling diver over the late-night TV host!

Dr. Edward Petuch at Florida Atlantic University reached out to GSML to make sure they knew the correct species ID for Abraclam. He is well-known for his work describing the change in ecology of mollusks in Florida and the Caribbean over the last several million years. GSML expressed interest in working with Dr. Petuch in the future, and I can confirm that I’ve had fruitful scientific collaborations start when other scientists have reached out to me about how I was totally, embarrassingly wrong. Being wrong in science is part of the job, and that’s why I’m glad this Abraclam story came out in the first place.

“So what does your son do? He’s a marine biologist. Does he work with dolphins? …I’m gonna say yes.”

-Stephen Colbert

To close out, I’d like to address Stephen’s assertion that my mom isn’t proud of me for being a clam expert. Stephen, I’ll have you know that my mom is the most enthusiastic patron of my clam science. She reached out to the local paper to anonymously tip them to interview me about my clam work, had me give a speech about clams at the local women’s group she’s a part of, and when I defended my PhD thesis, she made t-shirts to commemorate the occasion. I can confidently say I wouldn’t be Dan the Clam Man if it weren’t for her support. Thanks Mom!