Every clam is a door into the sea. If the “door” of its shell is open, the clam may be happily breathing, or eating, or doing other weirder things. If the door is closed, it may be hiding from a predator, or preventing itself from drying out at low tide, or protecting itself from some other source of stress. It turns out that by monitoring the opening and closing of a clam’s shell valves, a field called valvometry, scientists can learn a lot about the clam’s physiology, its ecology and the environment around it.

Valvometry involves attaching waterproof sensors to each shell valve of the bivalve, to measure the distance between them and their movement. Researchers have used valvometers to figure out that bivalves can be disturbed by underwater pollution like oil spills, harmful algal blooms, and more unexpected sources such as noise and light pollution.

Giant clams are a group of unusually large bivalves (some species reach up to 3 feet long!) native to coral reefs of the Indo-Pacific, from Australia to Israel. They grow to such large size with the help of symbiotic algae living in their flesh, the same kind that corals partner with the corals that build the reefs. The algae photosynthesize and share the sugars they make with their host clam, and the clam gives the algae nitrogen fertilizer and other nutrients, a safe home from predation and even helps channel light to the algae using reflective cells called iridophores.

Previous studies have used valvometers on giant clams, but I was always perplexed by how few studies there were: only two that I know of! One study on clams in New Caledonia figured out that the clams partially close every night and bask wide open during the day. The clams’ shell opening behavior and growth was found to become more erratic at temperatures above 27 °C, and when light levels become too great. Another study showed the clams start to clam up when exposed to UV light to protect themselves from a sort of sunburn, which is a real threat in the shallow reef waters they live in.

There is clearly a lot of information to pick up about how clams react to their environments, which can help us understand the health of the clams and also the corals around them. Coral reefs are under global stress from climate change, overfishing and pollution. Giant clams are some of the most prolific and widespread bivalve inhabitants of reefs, and represent an appealing potential biomonitor of reef conditions. Many giant clam species are threatened by the same stressors that influence the corals which build the reefs they live on, as well as overharvesting for food and their shells. For that reason, wild examples should clearly not be bothered by applying valvometric sensors. But giant clams are increasingly grown for the aquarium trade, resulting in a wealth of cultured specimens which could serve as sentinels of reef health, if they were fitted out with sensors. All of these motivators made me more and more curious of why we don’t have more literature monitoring the behavior of these clams with valve sensors.

I wondered if one of the limiting factors preventing the use of valvometry on giant clams is expense and ease of access. Giant clams live primarily in regions bordering developing countries in the Indo-Pacific, and almost all the professional aquaculture of clams for the reef trade happens in such countries, including places like Palau, Thailand, and New Caledonia. These countries are far removed from the places where most of the proprietary valvometric systems are manufactured. These systems can cost several thousand dollars even in Europe, never mind Palau, where arranging the import of electronics can be difficult.

When I started my postdoctoral fellowship at Biosphere 2 in 2020, I set out to grow two dozen smooth giant clams (Tridacna derasa, a species which can grow to about 2 feet long) in the controlled environment of the Biosphere 2 ocean, a 700,000 gallon (over 2.6 million liter) saltwater tank used to grow corals and tropical fish and kept at a stable year-round temperature of 25 °C. We suspended a series of LED lights intended to simulate the powerful light levels these clams experience in the wild (light is a lot brighter in the tropics than it is in Arizona!). The main focus of my project involved measuring the shell chemistry of the clams, to determine how their body chemistry changed as they grew from mostly getting their energy from filtering algae food from the water like other clams, to getting most of their energy from sunlight like a plant. But as a “side project” I set about measuring the behavior of the clams with custom-built valvometers based on open-source, inexpensive hardware that would be more accessible to researchers in the developing world. That work has since been published in PLoS One!

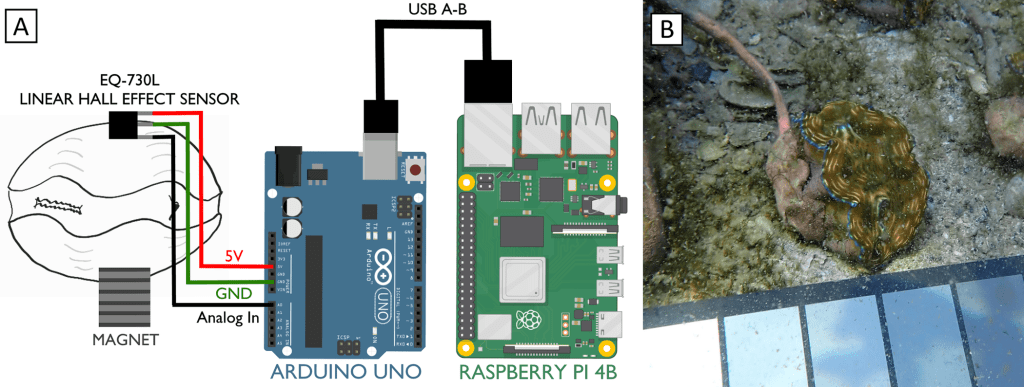

In our design, we used Hall effect sensors. Hall effect sensors generate a voltage when a change in magnetic field is detected. They are cheap, easily obtained for less than $1.50 apiece and are common in the electronics hobby trade. You might have encountered one in a home security system door/window sensor, where they help detect if a door is open or shut. We stuck a hall sensor soldered to a long copper cable to one valve of a clam, and a small magnet to the other valve. When the clam closed, we could measure exactly how closed it was. You can see why I started off by calling clams doors into the sea: we were literally measuring them that way!

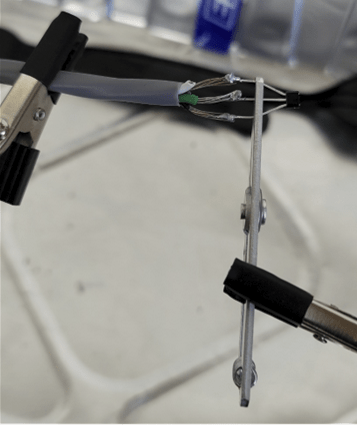

But here the first challenge of my project appeared. The off-the-shelf Hall sensors don’t come in waterproof form, and I learned quickly that the ocean really, really loves to break my gear. After dozens of failures, I settled on coating the sensors in waterproof grease, wrapping that in heat-shrink tubing and then sealing that inside of aquarium-grade silicone. During this process, a gifted technician at Biosphere 2 named Douglas Cline helped with iterating on the first prototypes. At a certain point I taught myself to solder so I could do my part to improve the sensors.

It was also hard to figure out how to attach the sensors and magnets to the clams in a durable way. Neither of the prior studies mentioned how they attached the sensors to giant clams, and I tried and failed with literally a dozen different ways before settling on “pool putty,” a two-part adhesive often used to seal leaks in pools that can cure underwater. I found the pool putty had trouble attaching to the clams’ shells on its own, so I combined it with a special kind of cyanoacrylate superglue called “frag glue,” often used to attach pieces of corals to growth stubs. I also had to find a way to attach it to the clams without stressing them out. I determined five minutes out of the water was enough time to get the sensors attached to the clams, after which they could be returned to the water to finish curing. While giant clams are adapted to spend extended periods out of the water in their natural intertidal environment, we wanted to make sure to minimize their stress however possible, to ensure they would show natural cycles of behavior in the data.

We were pleased to see the cyborg clams seemed to pay no mind to the sensors. Giant clams are adapted to encourage all sorts of other critters to live on their shells as a form of natural camouflage, and I think the clams interpreted the sensors as pieces of coral or anemones sticking to the side of their shell. Whatever the case, as long as we kept the cable pointing to the side away from the clams’ flesh, they opened five minutes after being returned to the water, and their behavior and growth rates were indistinguishable from the clams that didn’t have sensors attached.

So how did we measure the voltages coming from the sensors? Our design featured an Arduino microcontroller, sort of like a smart circuit board which can measure the voltages coming back over the copper cables. Arduinos are very cheap, and we chose a $25 model. Even more importantly, Arduino has a huge library of plug-ins available to keep the exact time of each observation using a clock attachment, and the data can be uploaded to SD cards or an attached computer. For the attached computer, I used a Raspberry Pi computer, which are open-source Linux-based tiny computers that are very cheap! Or rather they were very cheap before the pandemic, but fortunately there a lot of open-source alternatives that can be obtained more cheaply. We logged the data on the Raspberry Pi as it rolled over from the Arduino, and I could watch the read-out on a monitor right on the Biosphere 2 beach. We set the Arduino to record every 5 seconds.

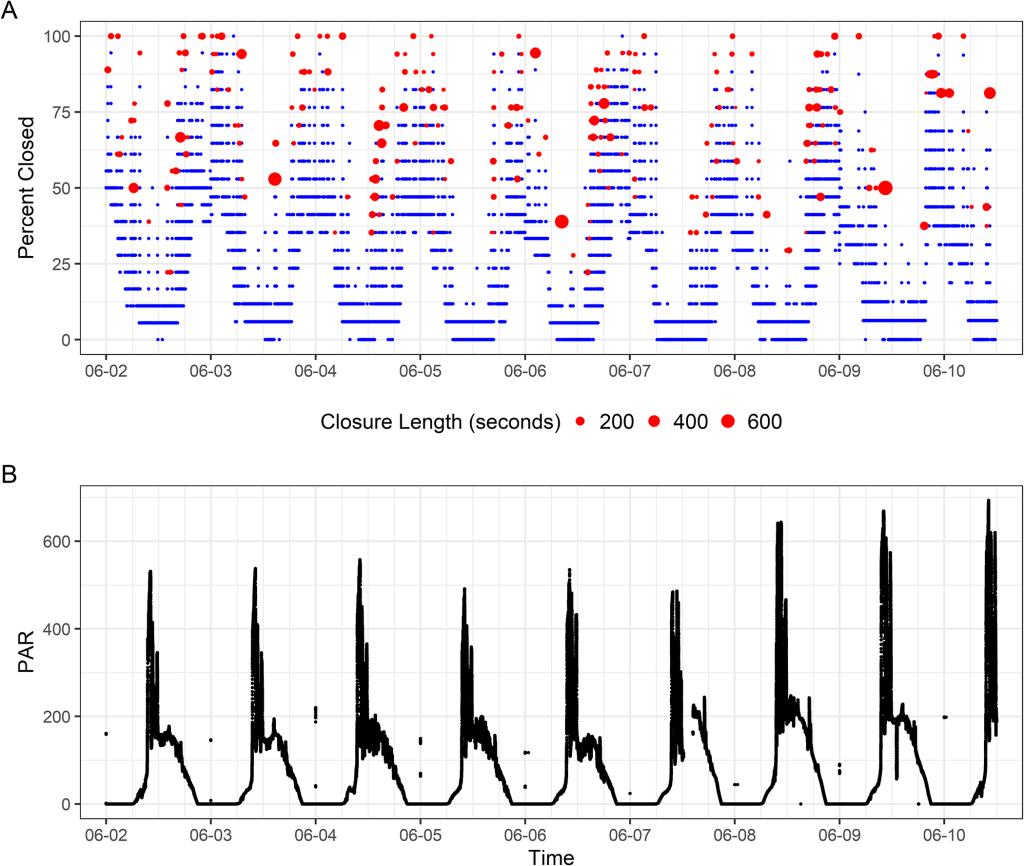

We ran the sensors for three months. During that time, the baby giant clams grew almost an inch! What did the sensors record them doing? During the day, the clams basked wide-open, exposing as much of their tissue as possible to light (other than the times that I disturbed them by swimming above them, of course)! This schedule of opening aligned pretty closely with the times that maximum sunlight hit their part of the Biosphere 2 ocean: the mornings, because the clams were on the east side of the building. At this time of day, the clams want to expose their symbiotic algae to as much light as possible, so they can conduct photosynthesis and make sugars that the clams use as food!

Around mid-afternoon, the clams started to close partially, to about half closed. Why might that be? My hypothesis is that this posture represents a kind of “defensive crouch” to protect themselves from predators, in this case fireworms that live in the Biosphere 2 Ocean and were constantly kicking the clams’ tires. Similar nighttime behavior was observed in wild clams in a previous study, but not in a study that took place in a small predator-free terrarium tank. By remaining partially closed, the clams are prepared to rapidly close completely if they feel a predator approaching. But they only expend that energy of staying in that posture if predators are around!

And approach the fireworms did. We observed frequent closures at night lasting anywhere from a few seconds to hours, likely partially related to the activity of the worms around the clams. But the clams were engaging in another activity at night: filter feeding! Giant clams really get to have their cake and eat it too, because during the day, they act like a plant, but at night, they eat other plants in the form of plankton that they filter feed out of the water using their gills! At regular intervals, the clams need to clear uneaten material from their gills in a process sometimes called “valve-clapping”. The clams yank their shell valves together rapidly to force water out, blowing out pseudofeces: unwanted material packaged with mucus. We measured this valve-clapping mostly at night. The clams are likely scheduling this activity for the night-time so they can prioritize staying open and filter feeding during the day!

We observed that the frequency of valve clapping aligned closely with the rises and falls of chlorophyll concentration in the Biosphere 2 ocean, which is a measure of how much plankton is in the water column. The clams would engage in a burst of valve clapping around 4 days on average after a bloom in chlorophyll, suggesting they were filtering out plankton after they had died and settled to the bottom where the clams could eat them. We also found that the clam’s filtering activity peaked at times of highest pH. This likely is due to the fact that higher pH means the algae around the clams are being more active, and pulling CO2 in from the water to use in photosynthesis, making the water less acidic. More photosynthesis means potentially more material for the clams to filter through! This data helps quantify how giant clams help filter the water in their native environments! Coral reefs depend on very clear transparent water to allow maximum sunlight to reach the corals, and the filtering activity of giant clams likely plays a big role in helping preserve those conditions!

So we found that by adding sensors to clams, we could record their ability to feed from the sun, their feeding on plankton around them and their avoidance of predators. How can this technique be used next? We hope that by using cheap off-the-shelf resources and open-source software, we can enable more sensors to be put on clams all over the world, such as places where giant clams are farmed in Palau, New Caledonia, Thailand, Taiwan, Malaysia and more! If we can collect data on clam activity from all these places, we can compare how their feeding patterns differ in places that have more or less plankton floating by, or have more or less sunlight available, or different predators that affect the clams’ behavior. This data would have importance to the clams’ conservation, as well as our understanding of the reef overall. In future years, I hope we can develop a global network of cyborg giant clams from the Red Sea to the Great Barrier Reef, so we can better understand how these oversized and conspicuous but still mysterious bivalve work their magic!