You are what you eat, and clams are too. We’re made of atoms, which come in “flavors” called isotopes, relating back to the mass of the atoms themselves (how many protons and neutrons they have). Nitrogen, for example, comes in two stable (non-radioactive) forms called nitrogen-14 and nitrogen-15. Much like scientists can track the composition of a person’s diet from the isotopes of their hair, researchers have used the isotopes of clams to figure out their diet.

Nitrogen isotopes provide us with a useful and detailed record of food webs. Plants and algae tend to have more of the light isotope of nitrogen in their tissues than the animals that eat them (primary consumers), and the animals that eat those animals have even higher nitrogen isotope values. We can measure the amount of “heavy” atoms of nitrogen with a unit called δ¹⁵N (“delta 15 N”). A carnivore at the top of the food chain will have a very high δ¹⁵N, while plants will be the lowest. Clams, typically being filter feeders, will usually have an intermediate value, since they’re eating a lot of phytoplankton (tiny microscopic floating algae) and zooplankton (animal plankton that eat other plankton).

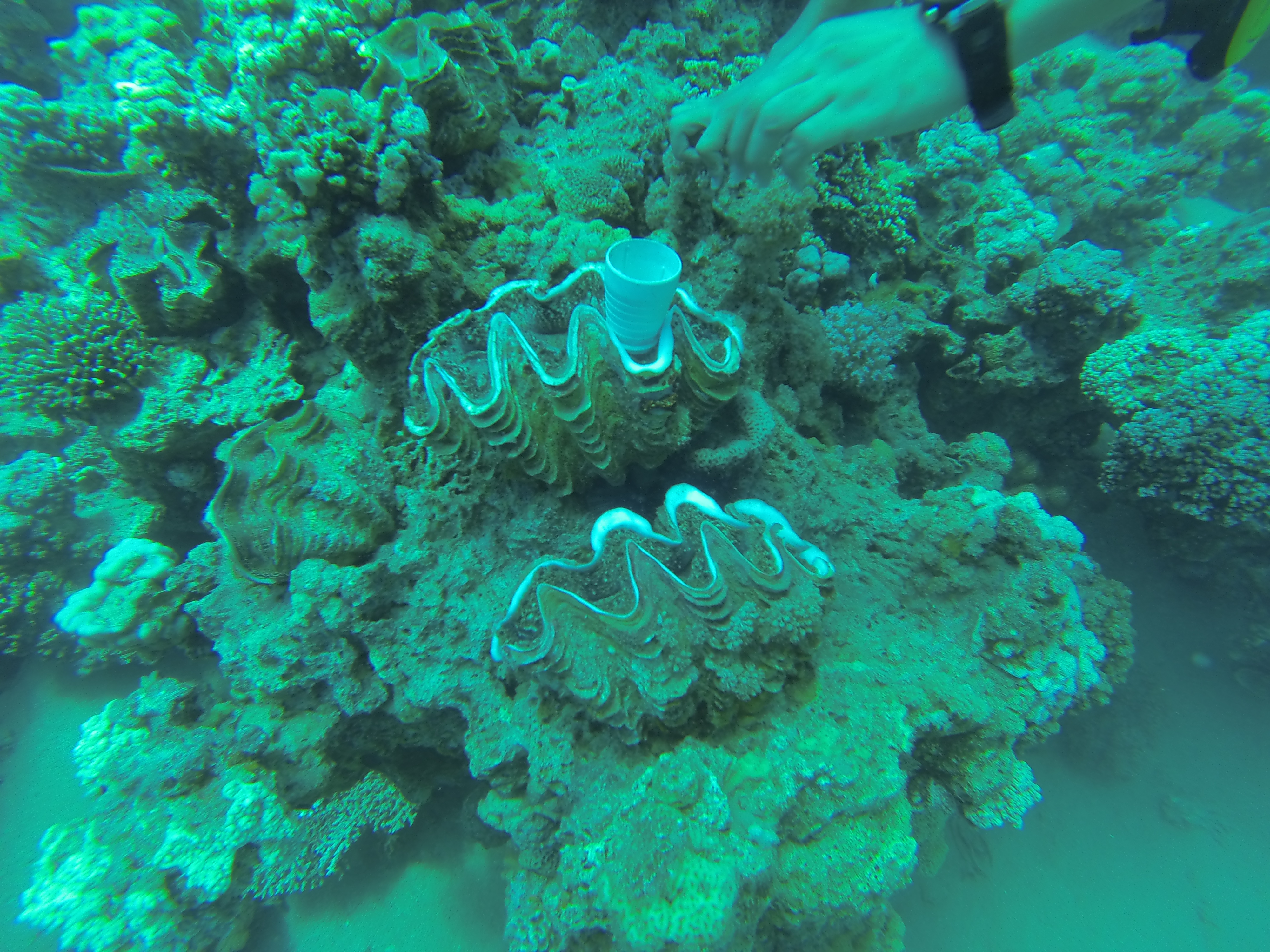

But I study a special kind of clam, the giant clams, which have a cheat code enabling them to become giant: they have algae *inside* of their bodies. The algae make food using photosynthesis and share it with their hosts! In exchange, the clams provide the algae with a stable environment free of predators, plenty of fertilizer in the form of their own waste, and even channel extra light to help the symbionts grow faster. This partnership is called photosymbiosis, and is pretty rare in clams, though it is common in other animals like the corals that build the reefs where giant clams are found! Previous researchers have shown that giant clams have very low nitrogen isotopic values in their tissue, like a plant, because they get most of their nutrition from the algae, rather than filter feeding.

I am a sclerochronologist. That means I study the hard parts of animals, in this case the shells of bivalves. Like the rings of tree, bivalves make growth lines in their shells which can serve as a diary of their lives. Some of my past work has looked at using chemistry of the growth lines of giant clams to measure the temperatures they grow at, compare the growth of ancient and modern clams, and even look at how much the clams grow in a day! Today though, I’m talking about my most recent paper, which looks at how we can use the shells of giant clams as a food diary.

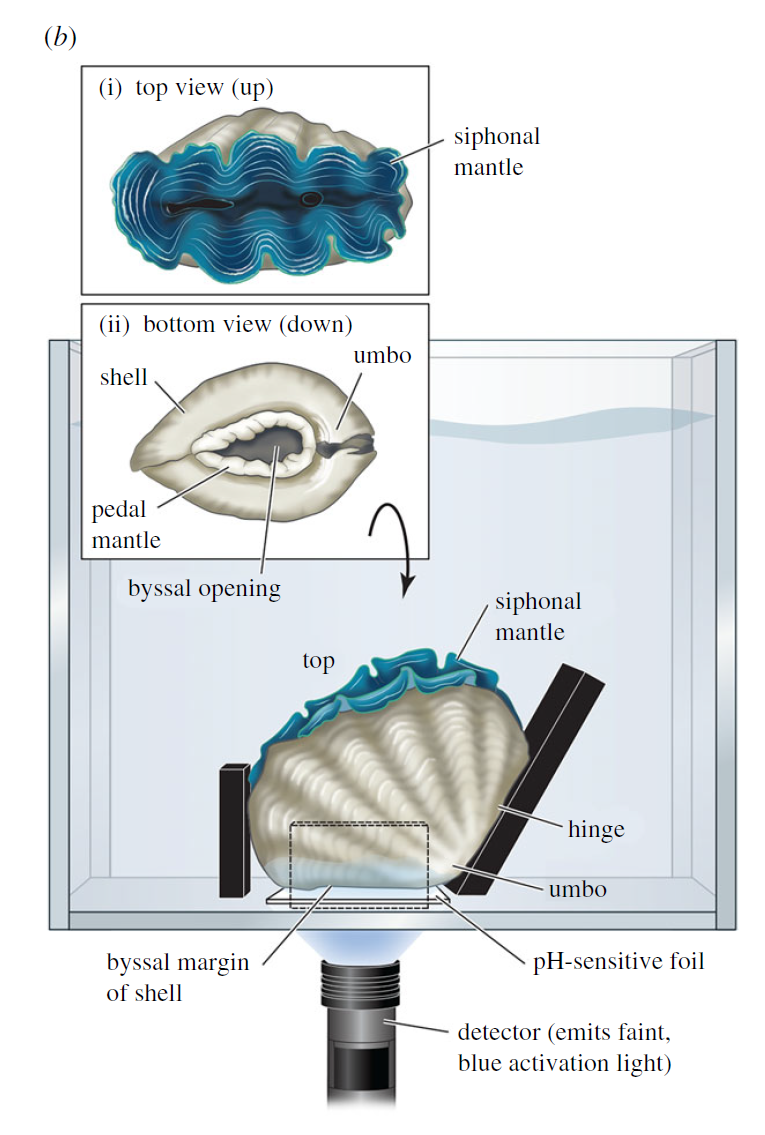

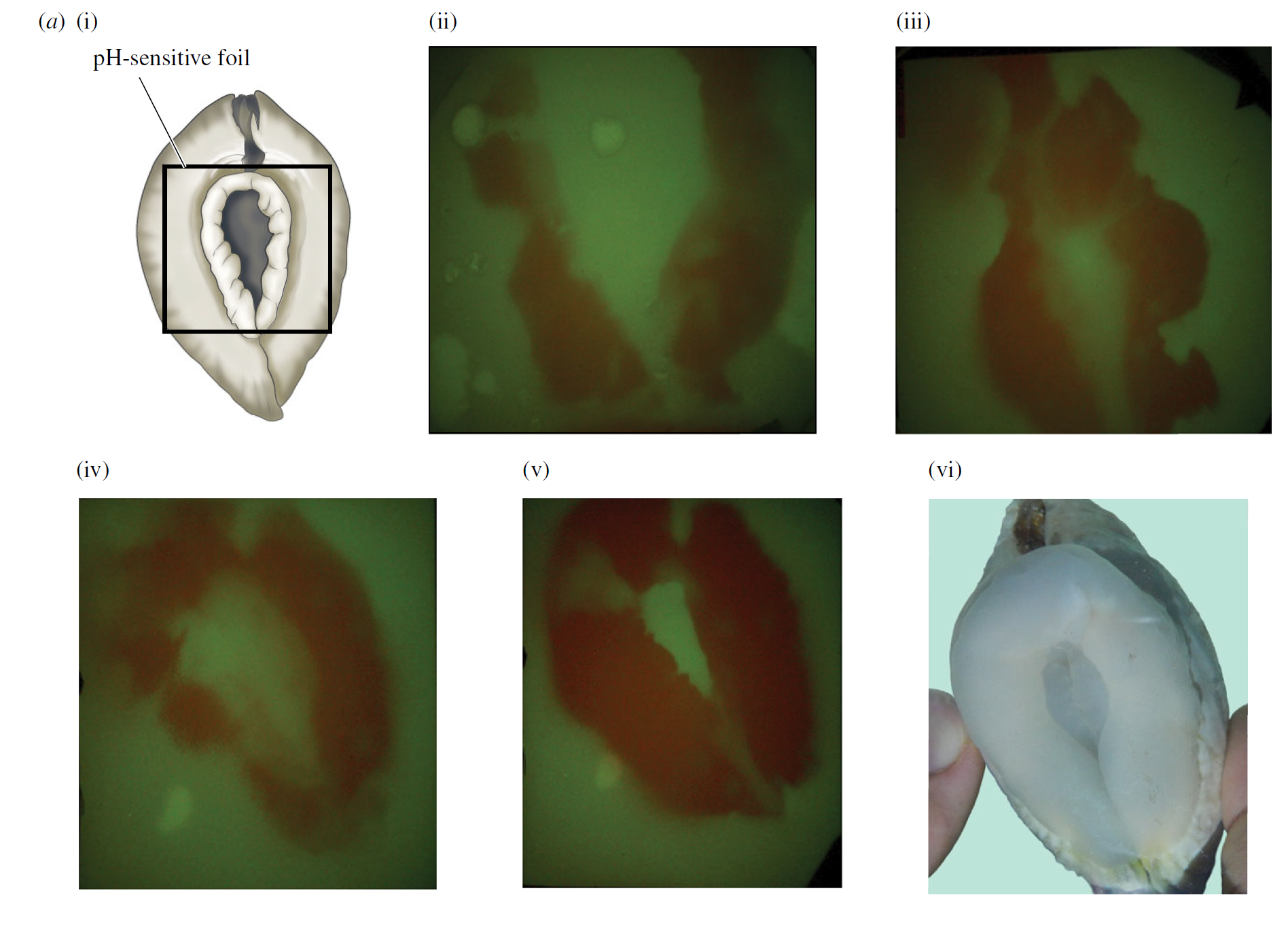

But when they’re babies, the symbiosis in giant clams is not yet fully developed. During this early period of their lives, giant clams actually get more of their nutrition from filter-feeding like a “normal” non-photosymbiotic clam, until they’ve had a chance to grow in surface area and become a living solar panel. Like all bivalves, the shells of giant clams are made of calcium carbonate, bound together by a protein scaffold we call the shell organic matrix. Proteins are made of amino acids, which contain nitrogen! If we can get the nitrogen out of the shell from the early part of the clam’s life, and compare it to the nitrogen at the end of the clam’s life, it might record the clam’s transition from filter feeding to its mature plant-like lifestyle! If our hypothesis holds, we should record a decrease through its life in the shell δ¹⁵N values.

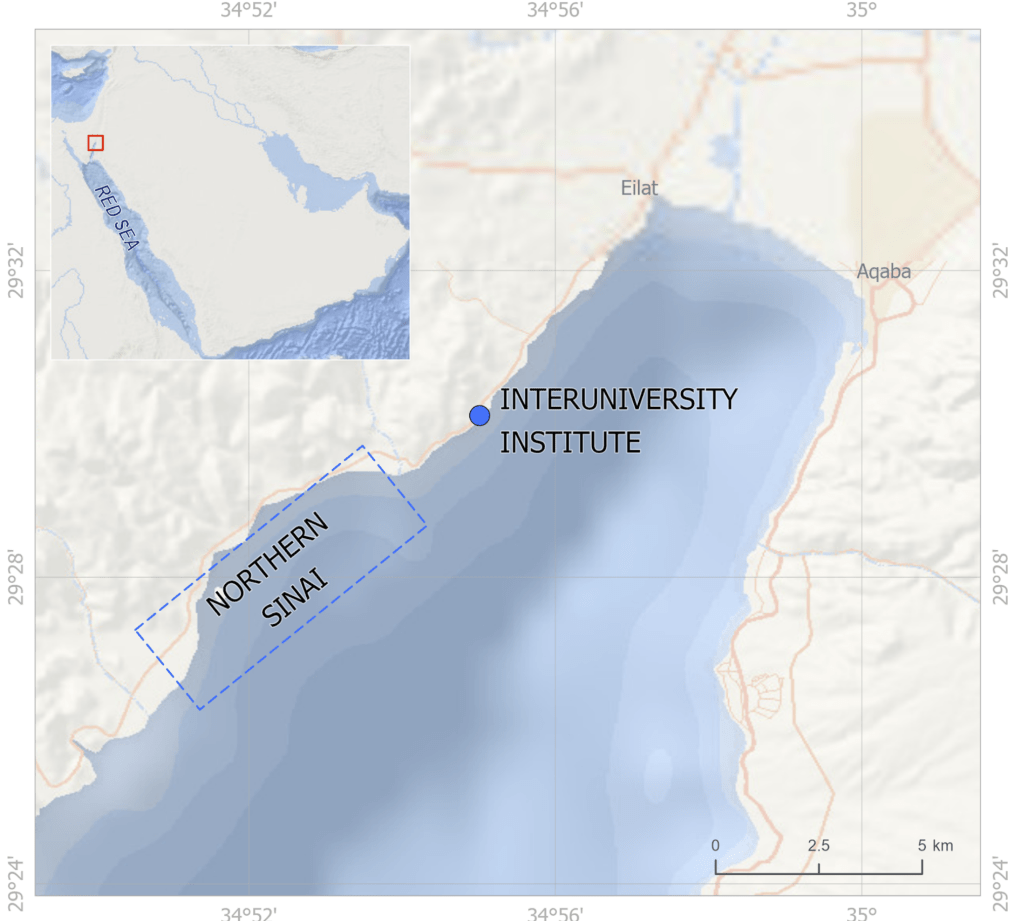

So I gathered a team of talented collaborators and set out to test that hypothesis, using giant clam shells that I was able to get on loan from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem Museum. These shells had been confiscated from poachers at the Egypt-Israel border. While I would have rather known these clams were still alive in the waters of the Northern Red Sea, being able to use them for research to understand the biology of their species was the next best thing! I had originally planned on pursuing a postdoc undertaking this project with Rowan Martindale, a professor at UT Austin who has studied the nitrogen isotopes of photosymbiotic corals, but when I started up at Biosphere 2, we ended up continuing with the project anyway as a collaboration! We measured the nitrogen isotopes of the shell material in the lab of Christopher Junium, a professor at Syracuse University, who has developed an exquisitely sensitive method to measure the nitrogen from shell material by essentially burning the shell powder and then scrubbing out unwanted material to isolate the nitrogen, to measure the isotopes in a machine called a mass spectrometer. Katelyn Gray is a specialist in isotopes of biominerals and assisted with drilling out powder from the shells with a Dremel. Shibajyoti Das, now at NOAA, is a specialist in measuring the shell nitrogen isotopes of other bivalves and he was master at doing much of the mass spectrometer work, and assisting in interpretation. Adina Paytan is a professor at UC Santa Cruz. She first provided the funding and support for me to go to the Gulf of Aqaba and collect these shells as part of an NSF-funded student research expedition! She also provided environmental data which helped us to interpret what the clams were actually eating!

So what did our crack team of scientists find out? We found that three of the four tested giant clams did indeed measure a decline in nitrogen isotopes over the course of their lives. Their earliest growth lines in the hinge areas of their shells record elevated δ¹⁵N values similar to other filter-feeders from the region. But as they aged, their later growth lines show much lower δ¹⁵N values, more like photosymbiotic corals and plants from the region. So clams indeed recorded the transition in nutrition as they became solar-powered! This degree and directionality of change in nitrogen isotopes was much greater than has been observed in any other clams measured in this way, which made sense considering their unique physiology. The clams have another area of the shell, the outer shell layer, which is closer to the symbionts than the hinge area. In this outer shell area, we did not observe much of a consistent trend in nitrogen isotopes. It’s likely that the outer layer is highly influenced by the photosymbionts even at the earliest stages of life.

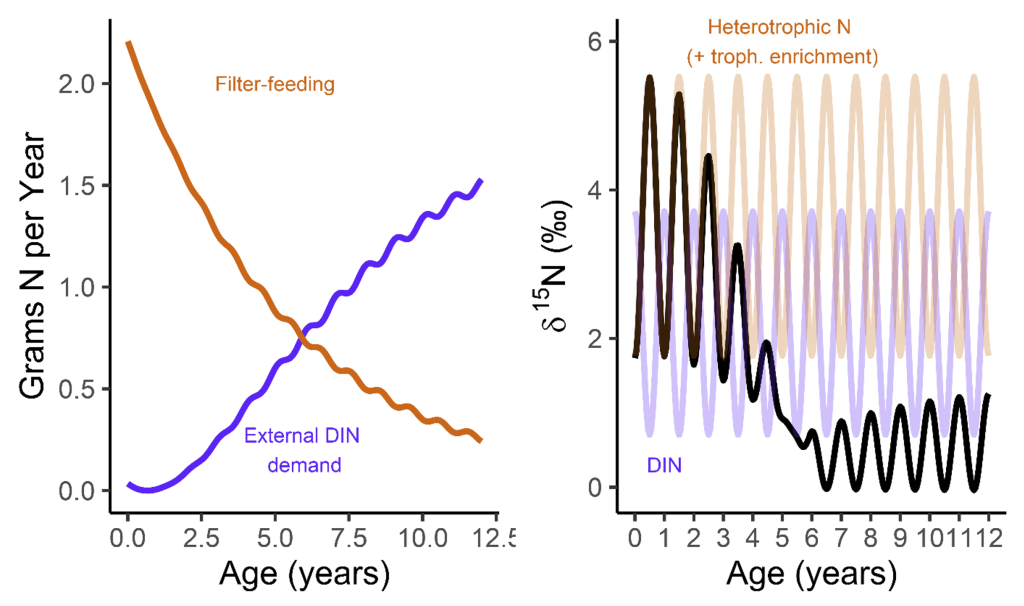

There was one clam that differed from the others in showing low δ¹⁵N values through life in its hinge shell layer. To help explain these differences, I created an independent model of the clams’ internal chemistry based on their growth rate, which slows as they age, and also is faster in the summer. When the clams are young filter feeders, they get most of their nitrogen from plankton, debris and other material floating in the water column making up floating material we call Particulate Organic Matter (POM). Meanwhile, when they are in their photosynthetic life stage, they get most of their nitrogen from nitrate, which is essentially Miracle Gro for the symbionts. The model showed that the clams should record a flip from filter feeding to photosynthesis around 4-5 years of age, which was confirmed by three of the shells! But what about the one that didn’t show this trend? My colleague Adina had fortunately measured the isotopes of POM and nitrate in different seasons in the Gulf of Aqaba. We found that in summer, as expected, POM δ¹⁵N is lower than nitrate. In the winter, meanwhile, that relationship is flipped! So if a clam grew more in winter, it would not record the same transition as was seen by the other clams. We think the clam that was the exception to the rule might have been more of a winter grower.

But long story short, we were able to demonstrate for the first time that giant clams show nitrogen isotopic values in their shells in line with expectations from their diet. Other clams have been measured this way, but the fact that we were able to conduct these analyses at all is a testament to the sensitivity of the elemental analyzer in Chris’s lab. Giant clams have *very* low concentrations of organic matter in their shells, so the forward march of technology was a major factor enabling this study to be possible.

Why does it matter that we can measure the transition of the clams from filter-feeding to photosymbiotic in their shell records? Well, giant clams are not the only bivalves which have photosymbionts. There are other clams in the fossil record which have been proposed to have had symbioses with algae, but until now we’ve never had a definitive geochemical way to measure this in fossils. We hope that this approach can be applied to the organic material in fossil shells, which is often well preserved, to see if huge clams in the Cretaceous and Jurassic had a similar way of life to the modern giant clams! If we can demonstrate that was the case, we can see how such species responded to past intervals of climate change, which will help us understand how giant clams will fare in the warming, acidifying ocean of the present.

These results also help explain the lives of giant clams themselves. We hope this kind of data can be used to measure the symbiotic development of giant clams in different places, with different types of food and nitrogen available, where we’d have the potential to measure pollution. Interestingly, the time that the model shows the clams transitioning to photosynthetic maturity is right around the time that they reach reproductive maturity (5-10 years of age). We’d like to investigate whether the time of clam maturity is controlled by the development of their symbiosis, which itself might relate to nutrients in the clams’ environment. If clams can grow faster, then they can mature faster, and potentially reproduce sooner in life. Will giant clams be able to thrive in the presence of increased nitrate, which is a common pollutant in coral reef environments? Like all worthwhile research projects, we have dozens of new questions to pursue as a result of this work, so stay tuned for the next installment in this journey of clam knowledge!